BOUNCING AROUND AGAIN

SARAH KERNOCHAN

With MARJOE (1972), her exhilarating exposé on the Pentecostal church, in which star-preacher Marjoe Gortner reveals his flimflam to the camera, Sarah Kernochan won an Oscar at a very young age. With Hollywood offering no opportunities, she started a career as a recording artist and as a novelist in seventies, after which she circled back to the movie business in the eighties. Her script for the wonderful period piece IMPROMPTU (1991), starring Judy Davis and Hugh Grant, was filmed by her husband, director James Lapine, and stands as one of the sweetest and funniest romantic films Grant has ever starred in. She wrote the final draft of 9½ WEEKS (1986), was asked to flesh out Jodie Foster’s character for SOMMERSBY (1993), wrote a CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND type ghost story for Steven Spielberg and saw her semi-autobiographical movie THE HAIRY BIRD a.k.a. ALL I WANNA DO (1998) buried by Harvey Weinstein. A few years later, in 2004, she won her second Academy Award, for her short documentary THOTH. Roel Haanen spoke to Kernochan via Zoom in February 2022.

How did you meet Marjoe Gortner and whose idea was it to make a documentary about him?

I made MARJOE with an older man [Howard Smith] who was my partner at the time and we shared responsibilities on the film. I was very young, about twenty-four, and I had a lot of ropes to learn. My partner was far more established. He had a radio show in New York where he interviewed celebrities and people of interest. And Marjoe had given up preaching for the millionth time and had come to New York to reinvent himself as an actor. But he quickly found it was very difficult to get the kind of attention he was used to as a star preacher and even a mega star as a child preacher. It didn’t sit well with him to go around, hat in hand, sending his photos out, not getting an agent. So, he thought: Let me do something that will get me some attention and then maybe my opportunities will come along. He approached Howard Smith with this scrapbook about his childhood, proposing that Howard do an interview with him. Howard brought the material home – we were living together – and said: I think this would make a good movie. Shall I give it to the Maysles Brothers? They were a documentary team back then who had made a film about a bible salesman. I said: They won’t want to do the same subject, so let’s do it ourselves. That was really naïve of me in retrospect, because why would I think we would get money to do a documentary about an evangelist? But indeed, there was one place who could conceivably be interested and they said yes. It actually came together very quickly. So, it came about because Marjoe was seeking publicity and he wound up with more he ever could have dreamed of.

He never became super successful as an actor, but he did have a career in the movies.

Yes, had he been a better actor he could have had a significant career, because the documentary was quite well known in Hollywood. He was invited everywhere. He was on the A-list of oddities you’d want at your dinner table. He could really regale people with stories about his double life as an evangelist slash hippie. He was offered roles right off the bat. But he was a much better preacher than he was an actor. His career really didn’t catch fire. He was always being cast as psychos and preachers. But it was his ambition to make it in the movies, which he achieved. He also says in the film that he could be a rockstar. And indeed he got an album deal from a major producer, but again, he just didn’t sing well enough.

Plus, the rest of the country really wasn’t aware of Marjoe at all, in spite of the fact he’d been in every magazine and newspaper. The distributor of the documentary chickened out and didn’t want to show it in places where the Pentecostal church could create a stink. So, in those states no one saw the film, until I repurchased the rights and had it released on DVD in 2015. Then, finally, people in the Bible Belt saw it. I can’t tell you how many people contacted me to thank me for helping them tearing themselves away from a religion that had warped them. I got very little negative feedback, to my surprise. Because at the time, evangelism, which had been a fringe group when we made MARJOE, was the religion for some four out of ten Americans. We even had a Born Again Christian in the White House at the time. My documentary was re-released when evangelism was at its zenith. For half the country it was released for the first time and it found an audience right way. I’m still making money off of it [chuckles].

Marjoe Gortner

When you were shooting, did you have a clear vision of what the film was going to be?

Yes, we had a clear outline. With a documentary you can’t go much further than that, because you don’t know what’s going to happen. There was a list of things we had to get in order to form a story. When we got into the editing room, the editor, who only had three months to put it together, said: I don’t think you have a movie here, you only have interviews and performances. So, I came up with a second outline that plotted things in such a way that the audience might continuously be surprised.

More than thirty years later, you made another documentary, THOTH, for which you won your second Oscar. Watching MARJOE and THOTH back-to-back I was struck by how they’re contrasting companion pieces: Marjoe creates this persona and performance which he knows to be a lie, and S.K. Thoth does exactly the same thing but he knows it to be the truth of who he is.

That wasn’t my intent. I was just trying to help Thoth out, because he was a penniless street artist. I wanted people to see what he did, because there wasn’t another soul on the planet who could accomplish what he does, which is to play the violin while dancing while singing about very spiritual things in a made up language. He was trying to create an energy that people find transformative, whether they understand it or not. When I got into the editing room it struck me that, like you said, I was making a film about a great entertainer, just like with MARJOE. But as you say, one was a liar and a prevaricator, who was conveying things he didn’t believe in, the other was about trying to get to the deepest truth, both of himself and of human existence. Thoth went spiraling off into a state of pure being, where he didn’t feel people’s judgment anymore. I constructed both documentaries in the same way. There’s a series of revelations, so that every time you get tired of watching the performance we laid something else on the audience that would surprise and animate them.

I very much doubt if I ever make another documentary. Not simply because if I ever made a third one, odds are I was not going to win an Academy Award. [Laughs] As they say, quit while you’re ahead. But also because I don’t expect to meet another individual quite like those two again. I was simply lucky to be there at the right place and the right time.

When you won the Academy Award for MARJOE what did that do for your career in movies?

Nothing. We got an agent and a script deal, but only as a team. And I had left him and I didn’t want to work with him. People assumed, because he was an older man, and because he was a man, that he had done everything and that I was the cute little girlfriend who tagged along and who had helped herself to a screen credit. I wouldn’t say it was the opposite, but he was more the producer and I was more the director, in terms of creative vision. So, there were no opportunities for me whatever as a director. I didn’t even have any role models in movies, because there were no women directors back then. No one. There were female producers, few and far between. Some editors. Otherwise it was a very closed club. It didn’t upset me very much, because my ambition had never been to become a director, especially one of documentaries. Fiction was my game. I was a writer. As far as I was concerned, MARJOE was a piece I had written. Because I was writing songs in my spare time, I got a record deal. I left any thought of going into film behind when I became a recording artist. I was headed where I always thought I’d be headed, to become either a recording artist or a novelist. I became both. I put out two albums on RCA, which failed. Then I got a very nice publishing deal.

Sara Kernochan interviewing Marjoe Gortner for her Oscar winning documentary

You got the publishing deal for Dry Hustle in 1977. For readers not familiar: it’s the story of a young woman who learns to “dry hustle” from an experienced stripper. They go around the country coming up with elaborate schemes to get guys to part with their cash, without the women ever losing even one piece of clothing. The mood of the book reminded me of movies from the sixties and seventies in which characters are detached and uprooted, like FIVE EASY PIECES, CALIFORNIA SPLIT, MIDNIGHT COWBOY and SCARECROW. Were you by any chance influenced by those pictures or was that just in the zeitgeist?

I wasn’t thinking about movies at all, because this was based on something that happened. In a way I was back at doing documentaries. I was taking notes and recording and even participating in these cons that these hustlers were running across the country. I disguised very little. Often I used direct transcripts of the conversations. It was gonzo style writing, so I could portray that world accurately. I was just following the story, not the zeitgeist. But I was aware that it was commercial.

I bought the British paperback of Dry Hustle online, which has a racy cover. It’s like they marketed it in such a way that it was lumped in with The Happy Hooker and those types of books that were hip in the seventies. Was that the case?

No, it was an airport book, but so were many other books. It was the age of women’s soft erotic fiction. And I don’t know why the Brits made it look so trashy, they certainly didn’t have to. I know that cover and I hate it. It wasn’t marketed as trash in the U.S, but it was marketed as titillating.

There were plans to make Dry Hustle into a movie. Could you tell me about that?

Yes, the novel sold to the movies. I got a contract to write the script and to direct it. I wanted Margot Kidder to play the older hustler, but that was nixed by my producing company. So, then I went to Karen Black who desperately wanted to do it. That hit the trade papers before I had a chance to ask the producer. He was furious that I would go ahead and cast a part without checking with him. That was one of the things that made it fall apart. But it introduced me back into the game and got me some publicity. I was able to parlay that into a screenwriting career a few years later, after my second novel didn’t get published.

What was the second novel that wasn’t published?

It was called The Love Slave and in retrospect I’m glad it wasn’t published. I don’t think it succeeded in its mission. I think I would have been embarrassed by it if it had been published. I always wanted to be a novelist and when that book was canceled I couldn’t get a publishing deal anywhere. I had to start over again. So, I started over again as a screenwriter.

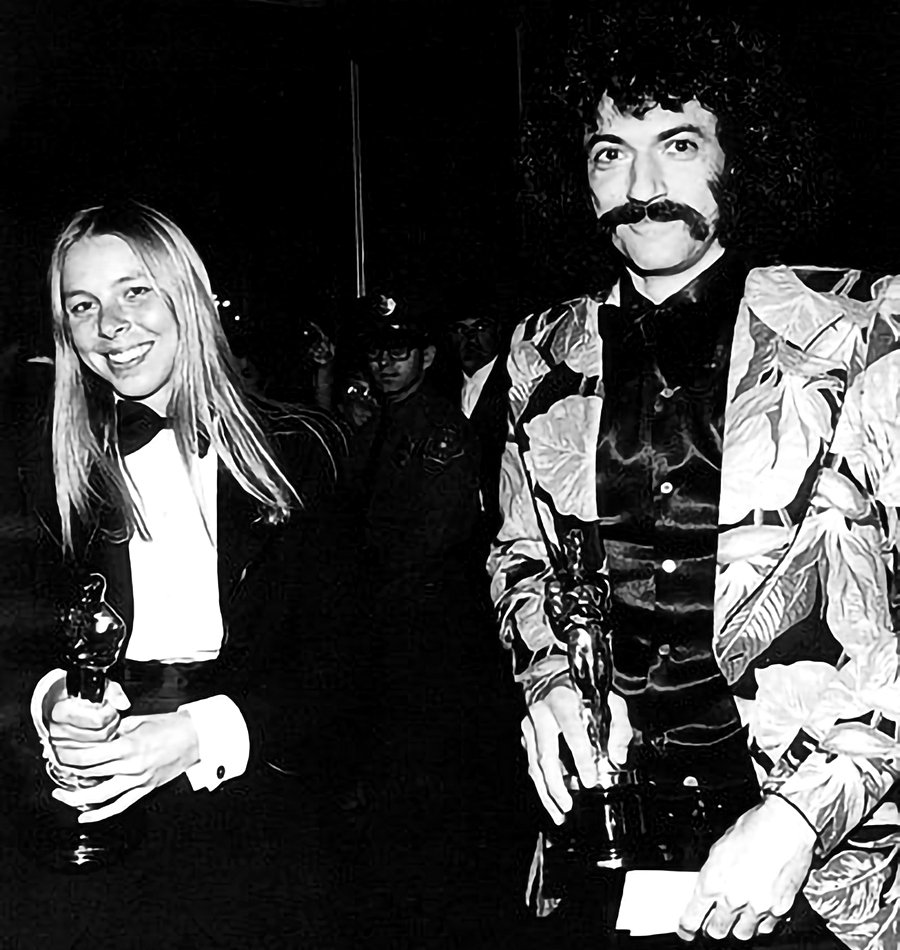

Sarah Kernochan and Howard Smith at the Ocars in 1973

What was the first screenplay that you wrote?

It never was produced, but it went through multiple directors, including Jean-Jacques Beineix who recently died. It was at MGM for a while. After the fourth director they got tired of it. It was about a psychic who began to manipulate a client she was in love with. When he breaks it off, she begins to stalk him. This was prior to FATAL ATTRACTION. Adrian Lyne did read my script before he hired me on 9½ WEEKS. He would never admit this, but I know some of the things from my script were lodged in his subconscious, because they wound up on the screen in FATAL ATTRACTION. It meant that my script would now never be done, because it would look like a copycat.

Did you ever say anything to him about it?

Oh no. Glenn Close is a very good friend and I wasn’t going to create a stink over that. It would not have held up in court, because it was just a few things. And also, if you go to that extent of suing somebody, you will never work in that town again.

Were there a lot of scripts you wrote that didn’t get made?

Of course, because that is true of every professional screenwriter. I think my ratio of produced to unproduced is pretty good.

So, Adrian Lyne hires you to write 9½ WEEKS. Were you the first writer to have a crack at the book?

No, I was the last. It’s a rather funny story. The second writer, who rewrote the draft by the first two writers, turned in a script that was due at the studio in three days. Adrian read it and hit the roof, because the guy had changed much more than Adrian had asked him to. He didn’t like the script. So, I got a call from a mutual friend who was an associate producer on the film, saying: I’ve got a weekend’s worth of work for you. Can you do it? I needed a new couch, so I took the job. Adrian and his cohort sat in one room and they were cutting up the two versions of the script with scissors and presenting me with the pieces they wanted to keep. I had to put them together and write the connective scenes to make it all work. That was the weekend’s work. It was turned in and the studio liked it. Adrian had come to like me, so he asked me to do further revisions to the point that by the time the cameras rolled I had written a third of it. It enabled me to get a screenwriting credit.

Kim Basinger in 9½ Weeks

Do you care for the movie yourself?

I think it’s really sexy, and I also think it makes no sense. Adrian in fact didn’t shoot much of the script. He went off his rocker a bit and wound up in the hospital with nervous exhaustion as a matter of fact. He was shooting all kinds of things, but not what was in the script, so it gave him a real problem in the editing room. The movie doesn’t make much sense to me, especially the last few scenes. That bothers me, but I can sit through it and find it incredibly sensuous, although the feminist in me hates it. But hey, it was a job and a paycheck.

It became one of these seminal eighties movies.

That’s not at all true. It was a tremendous flop in the theaters in the U.S. and it was roasted by the critics. People didn’t even want to be seen going into the theater to watch this movie, because it had a taste of S&M. It wasn’t until it hit Europe, where it became a sensation, that MGM realized they were actually making money off of it. It made stars of Mickey and Kim. When it came out on home video and people could watch it in the privacy of their homes, that’s when it found its audience over here. Americans are really weird about erotica. And 9½ WEEKS doesn’t even show any nudity. It finds other ways to be erotic.

But in terms of visual style, it did become a seminal eighties film, no? There’s hardly a movie from the eighties, TOP GUN maybe, that so sums up that commercial glossy style of Hollywood of that era.

Except it really wasn’t Hollywood at all that made the movie. TriStar was the company that had paid me and that was paying all the stars. But they backed out a couple of weeks before principal photography started, because somebody high up had read the script and said: Fuck no, we’re not making this. The producer had to run around Europe to try to get all the money from European distributors. That was one of the reasons Adrian was of out of his mind when they started filming. You may think it represents the eighties, but at the time it was abandoned and buried.

Mickey Rourke and Kim Basinger in 9½ Weeks

You wrote the script for the wonderful romantic film IMPROMPTU, starring Judy Davis and Hugh Grant. How did that come about?

I have Franco Zeffirelli to thank for it, whom I’ve never met. His associate producer approached me, saying: I have two film projects, which do you want? One was the movie that I picked, a ballet movie directed by Herbert Ross, starring [Mikhail] Baryshnikov. A very ill-fated movie. The other one, the producer said, was an idea Zeffirelli had, which was a big, sweeping movie about the affair between George Sand and Frederic Chopin. Before I picked one of the projects, I read a single book about their relationship and I became entranced by it. Because I saw something in it that was not what Zeffirelli wanted to do. Not at all. I knew he would turn my idea down. So, I said yes to the ballet movie.

The way I wanted to do that affair just stuck in my mind, but I didn’t think I was able to sell the idea to anybody. When the writer’s strike came along, in 1988, I had no work. My husband suggested I do something for myself. So, I wrote IMPROMPTU. I wrote it very quickly and it was a joy. I had never had that experience, being so immersed and so energized.

My approach to the material was that I saw it as a cross-gender movie. Chopin was the woman and George Sand was the man [Sand was the penname of writer Aurore Dupin who shocked 19-century France by wearing men’s clothing and smoking tobacco – ED]. She was the hunter and he was the prey. That really amused me. It’s not that I thought of it as a comedy – and the word dramady didn’t exist at the time – but the whole thing did made me laugh. I made sure those laughs were in the film. But in the end I found their relationship to be touching.

I also felt I could make free with the material in terms of inventing things, because there’s no historical record of their courtship. All the letters that were written between them were destroyed. There’s a two year gap in both of their lives. No one knows how that thing between them came about, so I was able to make it up.

Years before you took to the stage to accept your Academy Award dressed in a tuxedo. Was that just a coincidence?

[Laughs] I had never thought of that. No, I wore a tuxedo because I couldn’t afford a gown. I had a black pantsuit. I added my father’s cummerbund and bought a boy’s tuxedo shirt and I was off to the races.

Hugh Grant and Judy Davis in Impromptu

You wrote some fantastic dialogue for IMPROMPTU. What’s your process when you’re writing dialogue?

Damned if I know. It’s rather magical. If you have a command of your characters and you can walk around in their skin, they say what they say. You can almost sit back and take dictation. I taught screenwriting for a time, not too long ago, and I taught my students to interview their characters before they began writing. You’d be surprised by what they say. I’m not getting all weird here. They all reported that it worked. They asked questions that they didn’t know the answers to and the character would propose the answer. And they would write the answers in the voice of the characters, so that gave them practice at what that voice sounded like. It’s a mystery. Of course, if you’re writing you do want your characters to say certain things, because you want the scene to be about something, but sometimes characters can have a mind of their own and they won’t obey.

Did you consider directing IMPROMPTU yourself, instead of giving it to your husband [James Lapine] to direct?

Oh, never. He was amazing with actors and I was scared of them. He had a reputation already and people really wanted to work with him. Mandy Patinkin and Bernadette Peters had worked with him before, on the stage. They were the only Americans he was allowed to have in the cast, since it was financed with European money. It already had an American writer and an American director, so he was allowed only two American actors. I knew he could do a brilliant job with it, which I could not. I didn’t have the confidence at the time. Later I directed a script of my own, which I had much more confidence with because it was based on personal experiences.

What was it like to work creatively with your husband? Were you on the set to do any last minute rewrites?

Since it was his first movie he really didn’t want me around for the first three weeks, until he got his sea legs. After that I was allowed to be there. I was even an extra in one scene. I did make him nervous, because I was very proprietary about the script, unfortunately. He was aware of that. And he really didn’t want the feeling he was fucking up. I tried to stay in the background as much as possible. I didn’t do any on-set rewriting, except for one scene. That was the pivotal scene where Chopin finally responds to George Sand’s advances. James arranged for Judy Davis and Hugh Grant to rehearse that scene and improvise. So, I rewrote it, incorporating some of their improvisations. It greatly improved the scene, it really solved a problem. They were brilliant, both of them.

Judy Davis in Impromptu

So, I gather that you’re pleased with what your husband did with your script?

It’s probably my favorite thing I’ve ever written. That said, I think it was flawed. I just cringe when I watch the first ten minutes. I think it’s quite stiff and doesn’t have any forward motion. It takes too much time to get going. It’s off-putting to those who don’t realize that what’s coming is fun. But that’s probably just me. I think hardly any writer will look at their own work and say: That’s perfect!

Does your husband agree with you when you say the movie takes too much time to get going?

Probably not. [Laughs] Because then he would feel he was to blame and he’s not. I thought the writing could have been better in those scenes.

IMPROMPTU came out just before Merchant and Ivory hit it big with THE REMAINS OF THE DAY and HOWARD’S END and costume movies became fashionable again. What was the market like for your movie?

The distributor wasn’t very good, but it had its fans. It always had its little cult. People who say it’s their favorite movie. I’m approached sometimes by people who claim to know the script by heart. And I’ve tested them! It was well reviewed when it came out, but it wasn’t put in the right theaters. It wasn’t given an Academy campaign. Judy did win an Independent Spirit Award which should have led to some attention with the Oscars. The distributor just dumped it. That was disappointing. But when Hugh Grant became a star suddenly it had a new life on video. A lot of people watched it.

A moment ago, you mentioned working on DANCERS, which you called an ill-fated movie. I watched it and I thought almost everything about it was off. The actors were awkward, the editing was all over the place. I just didn’t understand how Herbert Ross could have directed this. Do you know what went wrong on that movie?

Yes, I do. It was the shortest script I’ve ever written. It was only fifty pages, because there was so much ballet in it. It was half a script and I wrote it really quickly. Herbert’s wife, Nora Kaye, had been a producer on Herbert’s other ballet movie THE TURNING POINT, also with Baryshnikov. That was a really good movie. She was dying of cancer and she wanted them to make one more ballet movie before she died. So, Herbert got Baryshnikov, he got the American Ballet Theatre Company, he got the stage in Bari in Italy, the largest stage in the world, other than the Met. But he didn’t have a script. So, the train was leaving the station, but there was no story. He gave me this assignment, which was that he wanted a mirror story to the ballet. He also said: Ballet dancers can’t act, so don’t give them any long speeches or anything difficult to do. He wanted a minimum of dialogue, which really tied my hands. I thought if I could add some humor, then it would seem less portentous. But Herbert wasn’t shooting for humor, because he was in the middle of a tragedy, with Nora dying, rather conspicuously, as we were filming. It colored everything. He had to go right into the editing room after she’d died. His mood very much infected the final product. The dancing in it is extraordinary. I knew the movie would come back as a record of Baryshnikov’s greatest performance. Because it’s his signature role and he was almost too old to be able to dance it.

Bahryshnikov and Leslie Browne in Dancers

Hearing this tragic backstory almost makes me feel guilty that I hated the movie so much.

Oh, apart from the dancing it’s quite a pathetic movie. I’m not ashamed of it, but I’m also pretty glad not too many people have seen it. If you had said that you liked it, I knew you were just trying to kiss my ass.

Also, Herbert Ross couldn’t be as good a director as he was, because he only had seven million dollars budget. He had never done a low budget movie before. He had never been so hamstrung. And on such a fast schedule. He couldn’t find his way in. He just had to keep motoring on, making the movie as fast as possible.

With SOMMERSBY you adapted LE RETOUR DE MARTIN GUERRE. How did that come about?

I was asked by the same guy who got me the job of writing 9½ WEEKS. He brought me in on SOMMERSBY, because they didn’t have a script that Jodie Foster approved. They wanted me to strengthen the woman’s character, but I ended up writing half of it, which got me a screen credit. It had been just a script doctor thing, but I ended up a co-author.

What were some of the changes you made?

In America, we don’t have any laws where you could be condemned to death for being an impostor. So, the original screenwriter made it a tale of murder. In the original screenplay the Gere character is guilty of the murder. In our version he was not. And I don’t think I would have done the project if they had wanted a happy ending. I always wanted to do it because it’s a tragedy. Americans don’t have a lot of experience with tragedy, because nobody dares to make a feel-bad movie. They’re born and raised on happy endings, which is regrettable, because tragedy has its place. Because the studio had agreed to kill off Richard Gere [chuckles], it made it very exciting for me. Also, one of my favorite plays is The Crucible. I gave his character the same choice: if he maintains his innocence, he will go to the gallows. If he admits he’s guilty, he will survive. He chooses his innocence.

Richard Gere and Jodie Foster in Sommersby

I may be digging too deep, but the man who pretends to be Sommersby discovers who he really is by being someone else. Thoth discovers who he is by creating an alter ego. Jane in your novel Jane Was Here discovers who she is after being reborn in a different body. Is that kind of self-discovery important to you as a theme?

My God. You’re really putting it all together.

You’ve never thought of this?

No, I’ve never made those connections. But I’m going to be thinking about this all day. You might be right about this. I always think of my career as being so checkered – bouncing from one genre to the next, of which I’m quite proud, because I don’t like to repeat myself – that I’ve never given any thought to there being a through line. You’re pointing it out, so that’s really… alarming [chuckles].

Let’s talk about THE HAIRY BIRD a.k.a. ALL I WANNA DO a.k.a. STRIKE! You prefer the first title. Which one do you like least?

STRIKE! That one never made any sense to me at all. Makes it sound like a working class political movie.

The genesis of this movie was autobiographical. Can you tell me which part of the story you lived through?

The story takes place at an all girl’s boarding school in the mid-sixties. That’s the school I went to. Everything about that school, from the uniforms to the prayer that they sing at dinner, all of that was out of my adolescence. The characters were wholly invented, although sometimes events that happened were worked into their story. I did have a friend who was bulimic. I grafted that onto a character I invented. My own self was divided evenly among the top five characters. That’s what you do anyway as a writer; you always invest something of yourself in your characters, even in the irredeemably evil ones. My school did go co-ed, but that was after I had graduated. I didn’t have that experience, but oddly enough I probably would have been in the camp of the girls that say: Sure, let’s have boys here! In retrospect I think being around only girls during that crucial time of my life saved me. That school saved me. As it was in the film the students had self-government, but it led to a spirit of all-for-one-and-one-for-all. That was really unusual at boarding schools. We were all rooting for each other. We told each other our dreams. I put that in the film. It sounds too rosy colored, but that’s what it was. And I wanted to show women coming together as a movement and helping each other. The film imagines that this generation – which was my generation – was going to be the one to kick through the ceiling and become the things we dreamed of. And it happened. My friend Glenn Close became a big star. Another friend became a State Supreme Court judge. Another one a highly regarded psychotherapist. That was unusual. The class before us all got married and had kids and kept their gardens going.

The Hairy Bird a.k.a. All I Wanna Do. From left to right: Heather Matarazzo, Monica Keena, Gaby Hoffmann, Kirsten Dunst and Merritt Wever.

Watching the movie I was wondering what Harvey Weinstein wanted with it, because it’s such a feminist movie. Not the kind of film a sexual predator would embrace.

Unless he wanted to get his hands on the actresses. They were all underage, except for Rachael Leigh Cook and Monica Keena. He did in fact cast Rachael Leigh Cook in a movie and turned her into a star. He did the same thing for Kirsten Dunst. So, he did help himself to my cast, but I have no idea if he came onto them. I think it excited him to have a female cast that young.

None of them had broken through at the time, right?

No, Kirsten was probably the one with the most public name, because of INTERVIEW WITH THE VAMPIRE. But she hadn’t had a breakthrough movie. He provided that for her, with BRING IT ON. He made her a star.

Did Weinstein mess up your movie? Or is the version out there your version?

I made many changes and reshot a few things at his behest, trying to placate him, so we could finally finish the movie and put it into two-thousand theaters, as he promised. But he just kept whittling it down, until it was under ninety minutes and he was still wanting to cut things. He demanded I cut a scene which he admitted was one of the most powerful scenes of the movie, a scene that totally succeeded. But he wanted to cut it for time. My producer said: Take out the scene and after that we will refuse to make any more cuts. That way we can tell him he has to release it. So, I took the scene out, as he asked, and he refused to release the movie. That scene is on my website, thank God. I will always miss that scene. He didn’t destroy the movie, but he did bury it.

I interviewed Penelope Spheeris a few months ago and she told me that the Weinsteins so fucked with her head – and with her movie – that it made her want to leave Hollywood altogether.

I hate hearing that he accomplished that with her. She’s such a good filmmaker. Hate hearing that. But my experience taught me a lesson. I learned that if you feel very strongly about keeping your vision intact, but you fear the repercussions, you shouldn’t give up your integrity. I should never have cut that scene, because he didn’t release the movie anyway. Had I stood my ground, it would have been the same outcome, but I would have kept that scene. Since then I’ve defended myself much better with people wanting to alter my work in a way I think is harmful.

Gaby Hoffmann and Kirsten Dunst in The Hairy Bird a.k.a. All I Wanna Do

Is that also the reason why you started writing a novel again?

Yes. You own your novel, but with movies you never own your work. Once somebody buys it and pays for it to be made, you don’t own it anymore. You may get the rights back if they don’t produce it, if you can afford to re-imburse them. It’s something you should realize before you start writing for the movies. You can’t get too precious and you can’t get too attached to your work. It doesn’t belong to you. A song belongs to you. A novel belongs to you. They can’t take it away and they can’t change it. The theatre is the best of all, because nobody can change a word of a play unless the playwright gives permission.

Is that so?

Yes, in America at least. It even applies to small amateur productions. They have to contact the playwright or the estate of the playwright if they want to make any changes. It’s really cool.

Have you ever thought of writing a play?

Actually, my husband and I are working on a musical together. It’s based on Nancy Drew. So, I’m bouncing around again. To the theatre this time.

Was writing Jane Was Here a joyful experience?

Yes. It was very hard, because I had to completely rewrite it after the first draft. It took me many years, because I was doing it in my spare time. I was feeding my spirit by doing it. It gave me freedom and a chance to use aspects of writing that you don’t use when you write for the screen. Screenwriting is like shorthand: you keep scenes brief, you keep descriptions brief, you have to write in a vocabulary that people who are not literary can follow. Screenwriting did teach me how to write plot. I know how to construct a mystery.

There’s one aspect in the novel that is pure literary and that is when Jane recovers a cache of old love letters and we learn about her previous life through reading all these letters. I loved reading those.

Those were the easiest to write, actually. Some readers didn’t like that at all. In cinematic terms it’s the flashback. If we were to do a film adaptation you would probably intercut with that story. It’s a bit Jane Austen, in contrast to the contemporary storyline.

Has Jane Was Here been optioned for a movie or television series?

No, alas. I keep wishing that would happen. But the pattern of my life seems to be that those things I think are dead keep coming back to life, so, who knows? I do have a pitch out there for a limited series, with a pilot script that I wrote, based on the book. Whether anyone takes it up, I don’t know. It was just something to do. It was fun.

Gaby Hoffmann, Lynn Redgrave and Sarah Kernochan on the set of The Hairy Bird a.k.a. All I Wanna Do

You have a story credit for WHAT LIES BENEATH. How much of the finished film is your story?

I would say my original screenplay was rewritten for about seventy-five percent by another writer. That whole ghost-taking-her-revenge plot wasn’t there. I wrote it for Steven Spielberg who has a very different taste than Robert Zemeckis who eventually made it. Steven approached me, wanting to do a story about a ghost who was an ordinary human being. The lead character was a woman who has just sent her kids off to college. She’s an empty nester. And the ghost that starts manifesting in her house, fills that empty space. He wanted it to be about the wonderment of discovery, of contact. Really what he wanted was CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND, but in an intimate domestic setting. My script succeeded in that, but when Steven read it, he realized it didn’t feel like a Spielberg movie. He didn’t know what he wanted me to do, because I’d already done what he asked. So, he gave it to Zemeckis, with whom his company had a deal. I was busy doing THE HAIRY BIRD, which was why they brought in another writer who pitched his idea for the movie. And that’s what they went for.

I think the movie has a strong build-up, but in the third act it just gets ridiculous.

I think of it as a B-movie with an A-list cast. I don’t relate to it that much. I see quite a few things in that movie that were ripped off from other movies, particularly DIABOLIQUE. But it was a nice paycheck and I had a really good experience with Spielberg.

All these different things you’ve done, artistically, does it have anything to do with your upbringing? Because your father also did a lot of different things in his life.

Oh yes. It was in fact the only way to get attention. I was very productive from an early age, whether it was making little movies or putting on puppet shows or making paintings. Every weekend I’d be doing something to get my parents’ eyes on me. They were very cultural and they applauded any artistic product. I got into that habit and I enjoyed the feeling that I could be good at any of these things. It made it very easy for me to switch from one discipline to another. The irony was that my father was not in favor of me going into anything creative. Not at all. Remember the era: this was 1967 or ’68. Nothing was particularly open for women, unless you put in an extraordinary effort and went through soul-crushing rejection. But I thought I was strong enough for it and he didn’t. I had the last laugh.

Michelle Pfeiffer in What Lies Beneath

Was he proud of your work?

Extremely. Remember, I had a big success right out of the gate. I was so young when I made MARJOE and then to get up there and win an Academy Award.

Did he like Dry Hustle?

Yes, he had a bawdy side to him. And my mother kind of shocked me by really liking the sex scenes. [Laughs]

Speaking of sex scenes, you wrote one of the funniest lines for a sex scene in LEARNING TO DRIVE, when Patricia Clarkson goes to bed with… I don’t know the actor’s name.

That was Matt Salinger, J.D. Salinger’s son.

That was Matt Salinger? He played CAPTAIN AMERICA once in a really bad movie.

Did he?

Anyway, he tells her he’s doing tantric sex and he seldom ejaculates. And then he turns around and says: What are you doing on Tuesday? I could ejaculate on Tuesday. That line cracked me up. It’s such a wonderful movie.

I of course found it disappointing, because too many things had been cut or not been shot. But I admire the director and especially the editor, Thelma Schoonmaker. We were so lucky to get her. She really made the movie sing. That was a good experience. If that’s the last screen credit I ever get, I’m fine with it being the last one.

From left to right: director Isabel Coixet, Sarah Kernochan and Patricia Clarkson on the set of Learning to Drive

Related talks:

This talk was edited for length and clarity.

Want to know more about Sarah Kernochan’s work? Visit her website at www.sarahkernochan.com. Her novels Dry Hustle and Jane Was Here can be purchased on Amazon.