DO THE PICTURE MY WAY

LARRY COHEN

About a year before his death in March 2019, around the time the documentary KING COHEN, about his life and work, was doing the festival rounds, Roel Haanen spoke to Larry Cohen on the phone. Cohen was one of the originals. He took the idea of monster babies and ran with it for three IT’S ALIVE-movies, every one of them working through a different parental angst with cleverness and humor. He also made the great monster movie Q THE WINGED SERPENT and the classic blaxploitation pictures BONE, BLACK CAESAR and HELL UP IN HARLEM. We almost would have gotten a Cohen scripted Marvel-film, but it wasn’t to be. The legendary guerilla film maker, who famously shot action scenes on top of the Chrysler Building without a permit, was still very proud of his achievements and rightfully so.

I’ve always thought of you as an unsung hero of cinema.

Well, now ’s the time to start singing!

With the documentary KING COHEN coming out, it is somewhat of a validation of your legacy. Were you pleased with the film?

Somewhat. I wasn’t involved in the production. They came to me and proposed the idea of doing a documentary and I said: sure, go ahead. But it wasn’t something I controlled in any way. I would’ve done it somewhat differently, but they did a good job and I was flattered by their effort. I think audiences are enjoying it around the world. It’s played in many countries now and the response is very good.

Do you think the documentary will introduce your work to a new generation of fans?

Sure, why not? What’s great now with the internet, the cable systems and BluRay is that my old films are available to everybody. All my films are coming out on BluRay, with my narration on them. Years ago you had to wait for an old film to play in a revival theater and sometimes they never did. But now you can just say my name on Netflix and fourteen titles pop up that you can rent and watch in your own home.

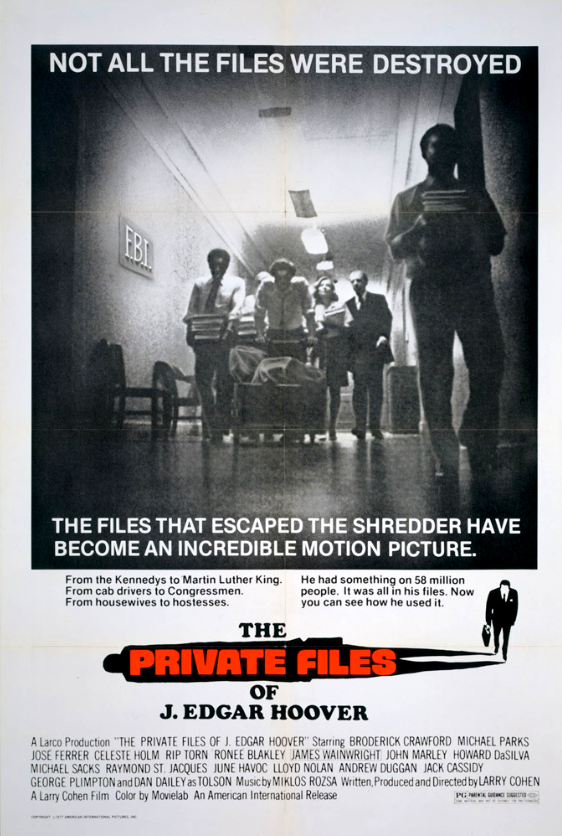

One movie of yours that isn’t easily found is THE PRIVATE FILES OF J. EDGAR HOOVER, which is a shame because it’s such a great picture.

It’s one of my personal favorites. It’s coming out on BluRay soon.

What I like about the film is that it’s so brutally honest: Hoover is portrayed as a complex guy with his good and bad sides, whereas the Kennedy’s aren’t portrayed as the saints some people believe they were.

That was the problem we had with the film in America. The Republicans didn’t like it and the Democrats didn’t like it, because we showed the dark underside of both political parties and of all the presidents. They were equally agitated, so they denounced it. Fortunately it played at the London Film Festival where it was a huge success and after that it played at some of the best British theaters. Eventually the BBC bought the picture. We had no problems there because the English weren’t involved in American party politics. They could just enjoy the picture for what it was. But the success in England was a bigger reward than I expected, because I knew when I started the picture it was going to be controversial. It wasn’t what people wanted to see. When we previewed the film at the Kennedy Center in Washington DC it enraged all the senators and congressmen that showed up, which I guess was the thing I wanted to do in the first place: make trouble.

I imagine you put in a lot of research into THE PRIVATE FILES OF J. EDGAR HOOVER, because your film contains certain facts that have only in recent years become widely known, such as the fact that Bobby Kennedy approved the wiretaps on Martin Luther King, or the suggestion that Mark Felt was Deep Throat.

Yeah, eventually Felt came forward and admitted he was Deep Throat, but we knew that back then. Nobody wanted to believe it. Least of all the Washington Post, because if it was known that Woodward and Bernstein had gotten their information from the FBI they wouldn’t have gotten any Pulitzer Prizes. They tried to silence that fact and they tried to silence the movie, but most of those people are gone now and the movie’s still here, so what can you say?

What did you make of Clint Eastwood’s film on Hoover? Some reviewers remembered your film and commented that it was superior and more entertaining. I think so too.

It was a very talented gay writer, who wrote the award winning MILK, who was obsessed with gay subjects and he tried to make the Hoover story about a couple of gay men, which wasn’t true anyway. As far as I could ascertain there was never a physical relationship between Hoover and Tolson. They were two old bachelors who liked to go to the ball game and the race track and that was it. There was no romance. All that stuff about Hoover putting on women’s clothing was a total lie. Every responsible historian has for the last fifteen years written that that was nonsense. Never happened. It was subject for late night comedians to tell jokes about and they perpetuated this falsehood. Along came Clint Eastwood and he made this movie and I was appalled. I knew Clint and I tried to persuade him, but I guess he had his reasons to do the film like this. He believed the writer of the screenplay more than he believed me.

Last week GET OUT received an Oscar and I couldn’t help thinking that GET OUT is exactly the type of picture you could have made 40 years ago. While a film like BONE was misunderstood, GET OUT wins an Oscar.

You’d be surprised to hear how many people have said to me that they think GET OUT is a Larry Cohen type movie, which is great compliment because it’s a very good movie. I have no idea whether Jordan [Peele] is a fan of mine or that he has seen my movies, but I would take a guess he has. Maybe I had some kind of influence on him. It was a very good film, I would have liked to have made it myself. It’s great to see a low budget film break out and win an Oscar and make that kind of money at the box office.

It was witty and smart too.

Yes, although I doubt whether putting people’s brains into somebody else is all that logical. And I think a girl sleeping with a guy for four months only in order to get him to her parents house is… Well, she sure put a lot of time into it. The other guy was just walking down the street when he was grabbed and thrown in the back of a car. So why take so long to get that one guy there? I guess it’s because the old guy wanted to get his photographer’s eyes. But even so, it didn’t have to take four months! And according to the photographs he found in her closet she was involved with an awful lot of black guys. I wonder if she spent four months with every one of them. She had an active sex life I take it.

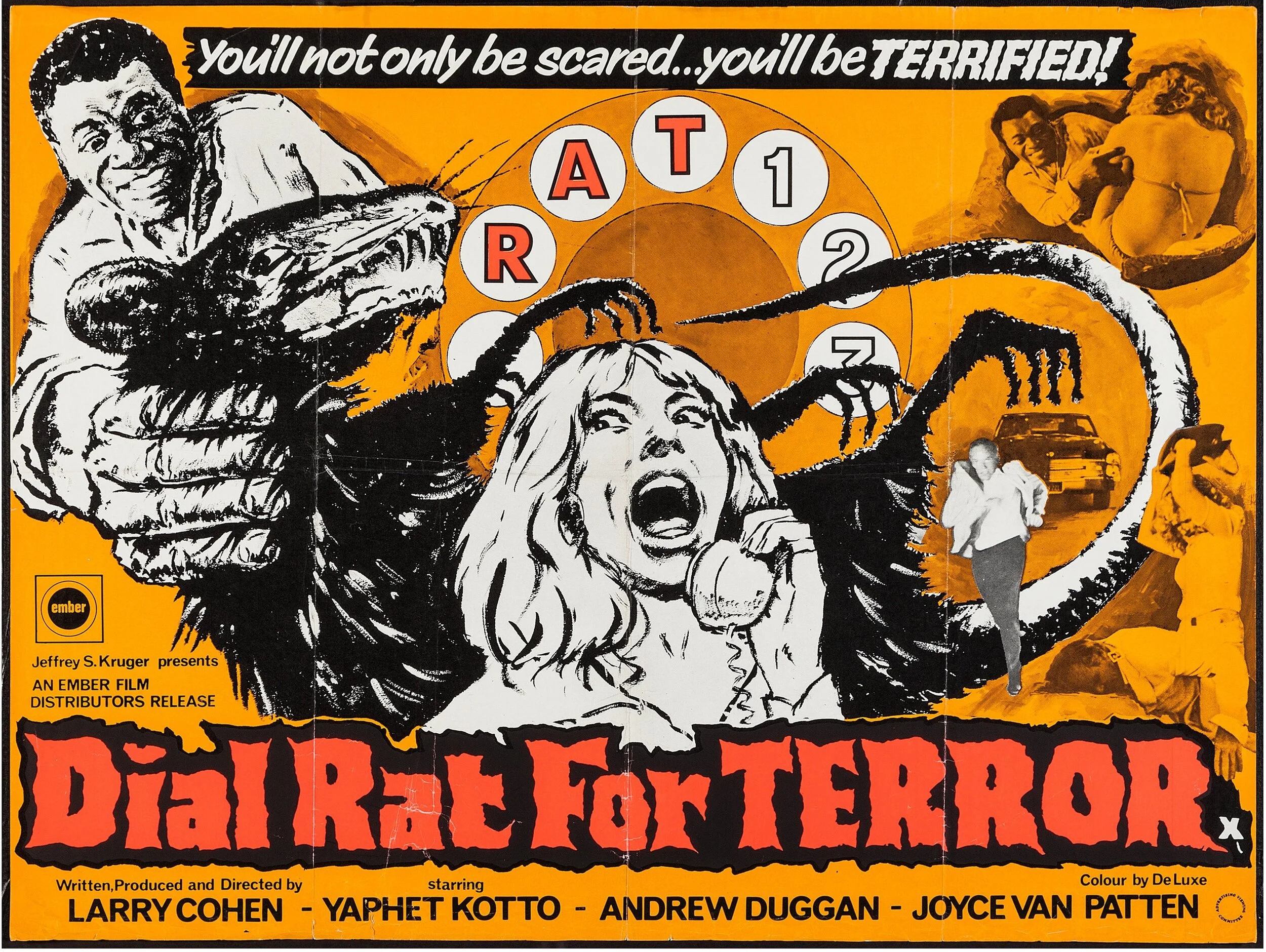

Yaphet Kotto calls you the white Martin Luther King of the Movies, to signify your importance for black cinema. How do you see your place in the black cinema of the seventies?

I think my movies were a bit different, in that I didn’t try to make the black character into a superhero. With BLACK CAESAR we made the kind of film they made at Warner Brothers with James Cagney. It was the rise and the fall of the black character. Most black action films of the time only showed you the rise. It was the only way I wanted to do it. I wanted a certain sweep to the story, with character development and a twist in the story. We were trying to make a first class movie.

As far as BONE goes, it is still ahead of its time because it deals with problems we still face today in America. The film is revolutionary because it cuts to the heart of racial prejudice. And some of that is indeed sexual, where the white man has a fear of the black man’s sexuality. It’s a thorn in the side of the white community. They’re still afraid of black people. In many cities white people will cross the street when they see black people coming. The black man’s power is what they’re afraid of.

Alternative poster for Bone.

And Yaphet Kotto was absolutely brilliant as black power personified.

He is the perfect image of the black man that white people fear. Perfect. I had interviewed Paul Winfield for the part but he was too genteel. Then I saw Yaphet in a movie William Wyler made, that very few people saw, called THE LIBERATION OF L.B. JONES, where he played a terrifying black man who put the sheriff in a threshing machine at the end of the picture. And I thought: this is the guy I want for BONE. If he’s good enough for William Wyler he’s good enough for Larry Cohen. And Yaphet says it’s the best performance he ever gave in his entire career.

I hope people continue to see that picture. Not many people saw it back then because it scared them. When it ran in a theater in Chicago a few years ago the manager told me that the white audiences were offended by the picture while black audiences enjoyed it. It’s still ahead of its time.

And the picture looks great. We had a wonderful cameraman called George Folsey who had numerous Academy Award nominations when he was over at MGM. He did amazing movies like MEET ME IN ST. LOUIS and GREEN DOLPHIN STREET and here he was working for me. I was so grateful.

You just mentioned James Cagney movies as an inspiration for BLACK CAESAR. What type of films inspired you the most to become a film maker?

I liked all the movies. I went every week and sometimes I sat through the film twice until they threw me out of the theater. The manager would say: Son, you have to go home now. I would say: I am home. But they threw me out anyway.

I particularly liked the Warner pictures because they were so fast paced and they had the actors I liked: Bogart, Cagney, Errol Flynn, Edward G. Robinson. They had a great roster of tough stars. And their energy was high-pitched. MGM was more genteel. Warner pictures had a real staccato style to them. Those were the kind of movies I wanted to make.

A lot of your movies have these far out ideas coupled with real characters. For example Q THE WINGED SERPENT: you have the idea for the flying serpent coming to New York. But how does that turn into a character study about a small time criminal trying to get back at the authorities he hates?

The development of that particular character came out of the wonderful actor I was working with, Michael Moriarty. Originally the character wasn’t a failed piano player, but when I discovered Michael wrote and played music we put that in. I wrote the extra scene where he auditions and fails to get the job. After that we just kept building on that. Of course, that character’s more important than the monster.

That reminds me: David Carradine once said that Q THE WINGED SERPENT would have been better if it didn’t have the monster. Now, I don’t agree with that, but…

I don’t either! What would it have been about? He had to have found the monster’s lair and blackmail the city! Don’t pay any attention to what David Carradine said. He was a friend of mine and he did the picture as a favor to me. He never even knew what it was about. He didn’t read the script. He flew in from Cannes and just showed up on the set. I just told him what to say and that was it. He never voiced any opinion about anything at the time. Except that he enjoyed working with Moriarty, in that Moriarty opened him up as an actor. You see, David was the kind of actor if you paid him he showed up. He did an awful lot of terrible movies. Thank God at the end he made KILL BILL. Aside from that one, Q is probably the best picture he ever did.

But there is something to be said for the fact that if Moriarty had given that performance in let’s say a court room drama he might have won an Oscar for it.

Well, in those days you didn’t win Oscars with low budget pictures. Today with something like GET OUT the rules have been broken. The genre has been opened up to more critical acclaim and that’s great. I hope it continues.

Michael Moriarty and Candy Clarke in Q The Winged Serpent

You worked with Moriarty four or five times?

Five. The last thing we did was an episode of Masters of Horror called PICK ME UP, which I think was the best episode of that whole thing.

What kind of man was Moriarty to work with? He’s had his difficulties.

He’s very difficult, but not with me. I always get along great with the actors who have bad reputations: Moriarty, Rip Torn, Michael Parks, Broderick Crawford. People who have trouble with everybody else usually have a wonderful time working with me. And I have a wonderful time working with them. I’m not an authoritarian director. I don’t go in trying to boss everyone around and play Otto Preminger. I’m having a good time with them, making up stuff for them to do. They love it when I sit down and write a scene for them right before their eyes, hand them a piece of paper with a hand written scene on it. The next day they come and ask for another scene. I like them to be involved in the making of the whole film. You know, making movies can be boring. The actors sit around all day reading paperbacks, playing chess or cards, they sleep, anything to pass the time between takes. On my pictures everybody’s working all the time. We’re making up stuff, doing things. It’s fun. They even show up on days they’re not working, just to see what’s going on! That’s the best compliment you can get.

So how does your process work? You get the idea for killer yoghurt. When you finish the script, do you already have a vision in your head of what the film is supposed to become? Or does it evolve while you’re shooting it?

With THE STUFF it happened almost the same way as with Q. The character I had written was not the same character Moriarty ended up playing. Right at the beginning he said to me: I think in terms of music. Can you give me something musical to hang on to? And I said: Let’s make the character a southern boy, we’ll call him Mo Rutherford. And as soon as he heard that it was a whole new story for him. And I kept making up stuff for him to do and say. Once again, we had a lot of fun making the picture. Making movies can become factory labor, if you let it. Actors in Hollywood usually work all the time and they give the same performance in every movie. One guy plays a cop in every movie, another guy plays a judge, yet another guy plays a lawyer or a doctor. It becomes boring. They’re always doing the same thing. So I try to give them something else to do.

Speaking of the same thing: nowadays, Hollywood is almost all about reboots and sequels. You’ve written a lot of sequels and even some remakes as well. What’s the most important thing when writing a sequel or remake?

In my case I usually had some more stories to tell. If you can’t carry the story forward there’s no reason for it. In the case of remakes, they’re usually not as good as the originals. I only wrote the story for THE BODY SNATCHERS. The screenplay, which I didn’t like, was done by other people. The only thing I contributed was the idea of the pod people on a military base, where you can’t tell the pod people from the regular people because everybody is a pod person. That idea is what convinced Warner Brothers to go ahead with the project. But then they lost all confidence in the project, because the studio was so incensed with the director [Abel Ferrara] who went way over budget and had a drug problem. They gave up on the movie, but when it was released it got some wonderful reviews. By then it was too late to give it a wide release and get some decent advertising for it. The picture kind of limped along.

Michael Moriarty in The Stuff: “Something musical to hang to”

Are you in any way involved in the MANIAC COP remake?

There is no such picture. I don’t think they ever came up with the money. Did you hear it’s being made?

No, I read something about it last year and assumed it was still in development.

Yes, last year. They didn’t ask me to write it. They got somebody else, without telling me. So I wasn’t too happy about that. I’ve been on bad terms with Bill Lustig who directed the original and who was supposed to raise the money for the new one. But the script didn’t turn out so well and nobody put up the money to make it, so that’s that. If they do make a picture I’d be very happy, because I’d get a big chunk of money. But if they don’t, so what?

There’s always the original, which was pretty good.

Second one was the best, I think. It was well cast, well made. The third one was terrible. They rewrote my script and fired Bill Lustig and they made a miserable mess out of it.

You’ve filmed a lot on location in NYC, often with permission or permits. The city has changed a lot during the last 35 years. Most of what you did back then would result in criminal charges today.

Absolutely! You couldn’t do what I did anymore. There’s camera’s on every corner and too much fear of terrorism. If you’re out on the streets with guns there’s gonna be a calamity. If you try to get up on the Chrysler building with machine guns, like we did on Q, you’re going to have a major terrorist threat. You can’t do that anymore. I was lucky I had that period in which I could do that kind of stuff. And the only reason I did it without permits was because we didn’t have the money to do it like a regular Hollywood film where you close down streets and bring in dozens of trailers, equipment trucks and dressing rooms. By the time you get all that on location you’re gonna have to close down a couple of city blocks. You’ll attract a lot of attention. So, you can’t do it that way without spending millions of dollars. I always wanted to do the picture my way and I didn’t have that kind of dough. And they came out much better I think.

Did you also shoot THE AMBULANCE that way in 1990?

In some of the cases we did get permits, but mostly we didn’t. We also didn’t have union crews and in those days you could get into a lot of trouble making a non union film in New York City. They would try to close you down. So we were harassed a bit. At one point they picketed us. So I went across the street and joined the picket line. They asked me what I was doing there. And I said: I’m the director of the film and I sympathize with you, so I’m picketing my own movie, okay? Eventually they got tired and left.

You made Stan Lee a supporting character. He played himself in THE AMBULANCE, long before Marvel became a big thing. Did you know him?

At that time Stan was desperately trying to get some of these characters made into movies. He was not having any luck at all. It was very frustrating for him. He had this deal with a producer to do a movie of DOCTOR STRANGE and I was hired to write the script. I wrote the script for the movie, which never got made, but in the process I got friendly with Stan Lee. We started socializing and going out for dinner and going to each other’s homes. Sometimes we would go out with Bob Kane, who is the creator of Batman. I had a great time with these guys. So when I was making THE AMBULANCE I said to Stan: I think I’m going to make this character a cartoonist who works for Marvel. I asked him to play himself. He was really anxious to do it. It was the only time Stan has had some real scenes to play in a movie and some real dialogue. In the Marvel pictures he’s mostly a walk-on or an extra. With me he had a real character to play, even if it was the part of Stan Lee. We maintained our friendship over the years.

I love how in THE AMBULANCE you used a color scheme that is very reminiscent of comic books, with the green, blue and red.

Yeah, I tried to bring that into the picture. I also used that old style ambulance. The new ambulances are just boxes on wheels. Not very interesting to look at. The old ones are sleek. So we used that, even though it wouldn’t be very logical for such an old ambulance to drive through the streets of New York City.

Eric Roberts and Stan Lee (playing himself) in The Ambulance

Fred Williamson once told me about the fight you had during ORIGINAL GANGSTAS and he said there was a physical altercation and he fired you.

No, no, no. We never had a fight. We had a disagreement. Fred was the producer on that one. He deserves a lot of credit for putting the whole thing together and hiring all the cast. He brought me in to direct the picture and he was going to be the producer. But he wasn’t much of a producer in terms of spending the money properly. He was only interested in making the film as cheaply as possible, so he could keep the money he didn’t spend. My interest was in making as good a picture as I could. That’s where we differed. He didn’t want to pay for air conditioning while it was a 105 degrees out! The actors were on oxygen! In one sequence we had a guy in a car firing a machine gun. Next day we’re ready to do the coverage and Fred comes in with a different car. I said: We can’t shoot this with a different car! The audience will notice it’s not the same car. And Fred says: Well, I had a fight with the guy who owns the car and he wouldn’t give it to me. So I said: You go back and apologize and get the right car! I’m not gonna shoot this. It’s stupid! You can’t have him in one car and then he’s in another car in the reverse shot. Things like that that were so inane. At one point I found out that Jim Brown was leaving. I said: He can’t leave, he still has three scenes to shoot. So I went up to him and asked him about it and he said: Fred knew I was leaving today. He had to go to some political rally in New Jersey. I asked: will you come back? He said: I’ll come back for one day if you fly me back. So I went to Fred and said: Listen , we gotta get a private aircraft and fly this guy back. Fred sure didn’t like spending that money, but we had to do it. I shot all of Jim’s last scenes in one day. If I hadn’t he wouldn’t have been in the last fifteen minutes of the movie. How can you send a star of the picture away without telling the director? I put up with all of it, but I got my way in the end. Today Fred is pretty proud of that movie, I think.

Well, it certainly is one of his better later films. He did a whole lot of films that weren’t that good.

Bad is the word.

Well, I must compliment you on your knowledge of all this stuff and the research that you’ve done. Because you certainly know the right questions to ask.

Well, I’ve been a fan of yours for a long time. I used to track down all your films in video stores.

Try to find SPECIAL EFFECTS and PERFECT STRANGERS.

I’ve seen SPECIAL EFFECTS, but I haven’t seen PERFECT STRANGERS.

PERFECT STRANGERS stars a two year old boy. I can tell you, directing a two year old who can’t speak is a major achievement.

Do you feel these two have been the most overlooked of all your films?

Probably, but then all of my films have been overlooked. We’ll see what happens next. So, where’s this documentary going to play? In Amsterdam?

Yes, at the Imagine Film Festival.

Well, give all the people there my regards and thank them for showing the picture. I hope they enjoy the picture.

Related talks

This interview first appeared in a shorter version in the Dutch fanzine Schokkend Nieuws. Above is the full version of this talk, edited only for clarity.