WHERE FATE HAS TAKEN ME

JACK SHOLDER

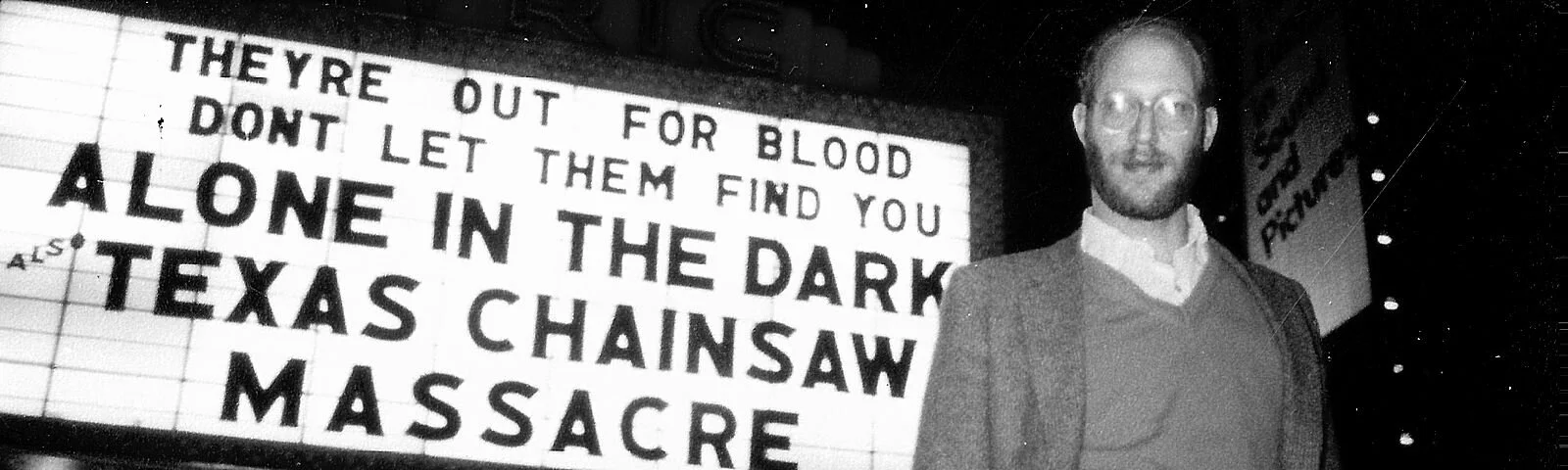

Photo courtesy of Jack Sholder

Many horror directors resent the fact that Hollywood had them pigeonholed. Given the chance, they really would have liked to do, say, a romantic comedy. But Jack Sholder never wanted to make any horror films to begin with. ‘Wes Craven expressed himself through the horror film, I expressed myself in spite of the horror film’, he says. Still, while Sholder’s most famous films, like ALONE IN THE DARK and A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET 2: FREDDY’S REVENGE, are within the horror genre, he did get the chance to do action (THE HIDDEN, RENEGADES), a romantic comedy sci-fi hybrid (12:01) and a particularly well made World War III drama called BY DAWN’S EARLY LIGHT. Roel Haanen had a talk with Jack Sholder about his career in September 2020.

So, are you retired from film making? Because you were a film teacher for a lot of years.

No, I’m not retired. I took a job to start a film program at a university in 2005. So, I moved to North Carolina. I basically put all my energy in that. I’d never taken or taught a film course in my life, so it was quite a challenge. I did it for fourteen years and then retired from the university three years ago. I hadn’t done a film in a while, so out of sight, out of mind. But I’ve had several film projects come and go since then. You know, indie stuff. There’s one that is supposedly getting made next summer, that I co-wrote. The producer feels confident that it’s going to get made, but if I had a dollar for every project that was gonna happen and then didn’t… Well… But, basically, I’m rewiring, not retiring. I’m at the point where there’s retrospectives of my work. Last year there was Rome, Sweden and this festival right here – [Sholder shows the t-shirt he’s wearing] – it’s called Night Visions in Helsinki. Great festival. At Fantafest in Rome I got a lifetime achievement award and they did a book.

That’s really cool.

Yeah. So, I’ve been doing stuff like that. Resting on my laurels, but I really feel that I’m not finished as a filmmaker.

So what’s the film you co-wrote that you hope to make next summer?

It’s a vampire movie. It’s based on a famous novel called Carmilla, which was written by an Irishman years before Dracula. It’s about a young girl who travels with her mother in a coach. They stop at a castle. They’re taken in. And there’s a young girl who’s the same age as the other girl. And they get into a thing. It’s been adapted a number of times. We’ve done our own spin on it.

You just said you have never taken a film class. So, how did you become a filmmaker?

The same way Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Jean Renoir and Akira Kurosawa did it. Originally, I wanted to become a classical musician. Then I realized I was good, but not great. And it’s a difficult life, so I decided to become a writer. Then at a certain point I had a girlfriend who was into film – this was at the University of Edinburgh – and I started watching films and I thought: Hey, this is really cool! I think I would like to do this. I came back to the States, and I was at the university as an English major. There was no film program. But I did do some short films. So, I graduated and moved to New York with the idea of becoming a filmmaker. I got some work as an editor. So, I did that.

I basically taught myself how to edit. Normally, you would get a job as an apprentice or assistant. That’s how you learned. After four or five years you would get promoted, when the editor would be too busy and he’d say: Why don’t you give this guy a chance. But I just started working and figured it out myself. I always thought I was a really good trumpet player, but I think my great talent was in editing. My problem as an editor was I always thought I knew more than the director. Of course, I never worked with any great director, but I had a big ego and I wanted to direct myself.

Another part of my education was watching movies. New York at the time had at least six good revival houses that played old movies, European movies, art movies. If I had a Netflix-account back then I probably wouldn’t have seen them, because I would’ve chosen something else. But I saw them, because they were playing. I discovered Andrzej Wajda, a Polish director who I think is one of the greatest directors ever. Someone had restored all of Buster Keaton’s movies, so I saw those as well. That was my education.

You edited some Japanese movies for the American market at the time, right?

Yeah, I did a lot of editing for New Line, when they were a small indie film distribution company. I did pretty much all their trailers. Sometimes a title sequence. Sometimes I re-edited the whole picture. There was this yakuza movie for which I supervised the dubbing into English. They gave me a credit as a writer. Not because they wanted to be nice to me, but they didn’t want the audience to think that this film was made only by Japanese people. They wanted people to think there were Americans involved.

Jack Sholder has a writer’s credit on the yakuza movie The Tattood Hit Man

How did you know [New Line founder] Bob Shaye? Did you just apply for a job with him?

A friend of mine from college, who had shot all the short films I did, had a girlfriend in New York who worked as a temp at New Line. They were just starting up. There were only about four people there in a small office. So, my friend said: why don’t you call them up and see if they’ll distribute one of your films. I called them and they told me to bring by the films. I brought over some of the ones I thought were the best. A couple of weeks later Bob Shaye called me and I went by the office. He said: I’m really not interested in your shorts. They’re well made, but I can’t use them. So, I thanked him and as I started to leave, he said: By the way, you know anyone who can cut a trailer? And I said: Yeah, me! I had never cut a trailer. I had been working as an editor in New York for about six months, working on low-budget stuff.

Cutting trailers was part of my education. If you wanna be a watchmaker, take a grandfather clock, take it apart and make a wrist watch out of it. That’s basically what making a trailer is. You learn which parts you have to cut together in order to make it tick.

After Bob and I had worked together on a trailer during a whole weekend straight, we sort of became friends and he adopted me in a way. I was living by myself, I didn’t know anybody in New York, I didn’t have any money, so Bob took me along wherever he went. He would invite me over for dinner, take me along if he was invited anywhere. He was really generous to me. And any editing work that had to be done at New Line, I would do it. I was part of his unofficial brain trust. If he had to make a decision about something, he would usually ask a few other people what they thought. I was one of them.

I got to meet a lot of filmmakers through Bob – not that I learned anything from them. But he was the first person to distribute John Waters, Werner Herzog. He knew a lot of people.

But Shaye also must have seen talent in you, because he gave you the opportunity to direct his first film production.

Yes. This is what happened: I was not part of the staff of New Line, but I hung out at their office a lot and I knew everybody there. They were sitting around after work one day and one of the execs said: You know, the distribution business is getting too difficult. They were getting a lot of competition from the majors, who were setting up their own classics divisions. And he said: If we could produce a feature film ourselves, a horror film, we could make a lot of money. Because New Line specialized in the youth market. They felt they understood that market.

Prior to that, Bob had taken me to see FRIDAY THE 13TH because he was blown away by it. He thought it was a pretty good film, but what blew him away was the fact that this film cost so little to make and made so much money.

So, I came back a few weeks later with the idea for ALONE IN THE DARK. Originally, it took place in New York City. There had been a blackout in 1978, where the entire island of Manhattan went dark. It lasted at least 24 hours. Some parts of Manhattan were out for three days. So, that figured into it. I said: How about a group of criminally insane that are kept in a hospital on Manhattan where the only security is electronic. They would have no bars on their windows, because they have this liberal-minded psychiatrist. When the power goes out, they escape. But meanwhile the whole world outside is going crazy, so they fit right in. But then they terrorize Little Italy and they are rounded up by the Mafia. That was my idea. Bob thought it was pretty good, but New Line didn’t want to shoot in New York City, because it was too expensive. Also, they were afraid the unions would see us. So, I revised the story to what it is now.

They told me that if they raised the money, I could direct it. I had done a short film called THE GARDEN PARTY, which is completely different from anything I’ve ever done. It’s a young girl’s coming of age, based on a famous short story by Katherine Mansfield. It won a bunch of awards and it played on television. You can see it on YouTube, by the way. I think Bob was impressed by that. He knew that I understood movies.

Around that time, a lot of people were making low-budget horror films, but most of them didn’t even know how to make a film. They would shoot stuff and then discover in the editing that they were missing pieces. They couldn’t get from this shot to that shot. They were not craftspeople. Bob trusted me with the film, because I was an editor and he knew I would get all the pieces. Whether the pieces would be any good, who knows? But at least he knew he would have a film. And the bar was not that high. He didn’t expect a masterpiece. Most of those movies are really pretty shitty. A lot of them are now considered cult favorites, but they are really not good films.

Jack Sholder’s short film The Garden Party

In the meantime, I went off and edited THE BURNING, which was the first film the Weinstein brothers did. I really wasn’t into the genre at all. So, I learned a lot about how horror films work. How to build suspense and stuff like that. There’s this scene in THE BURNING where these kids are on a raft and there’s a canoe on the lake. They start paddling toward the canoe. Of course, we, the audience, know there’s a maniac with gigantic hedge clippers. I edited the scene. And Harvey, who had never produced a movie before, told me it was too short. I had used what I thought were the best shots. So, I made it longer and showed it to Harvey. He said it was still too short. I had used all the good shots, but Harvey told me to use every shot I had. So I started adding all the other shots and the longer it got, the better it got! Because with suspense, you want to draw it out. Of course, there’s a point where it becomes too long. But it all goes back to Hitchcock and his bomb under the table.

I used this experience on THE BURNING to do a rewrite on my script. Make it scarier. I think I added the scene with the babysitter on the bed at that point. During the editing of the film, they kept saying that scene was too long. Why is she on the bed? As soon as she knows there’s a maniac, she’s gonna jump off the bed. And I said: If she jumps off the bed, you don’t have a scene. They didn’t think anyone was going to believe that she stayed on the bed. But I think it’s probably the most effective scene in the film. It always gets a great reaction at screenings.

With the rewritten script they were suddenly able to raise the money. I don’t know if it was the script or the timing. But I got to make my first feature, which was amazing. Especially with that cast.

I was going to ask about that. You had Jack Palance, Martin Landau and Donald Pleasence. Were they difficult to get?

No. Not at all. We had a producer by the name of Benni Korzen. He was Danish, but he had been living in America for lots of years. He actually produced BABETTE’S FEAST. He was hired because he claimed he could make it cheaper than anybody else. One day he came into my office and asked me what I thought of Donald Pleasence for the role of the psychiatrist. I thought Pleasence was one of the great actors of his generation. He was in CUL-DE-SAC among other films. He had done Pinter. I hadn’t even seen HALLOWEEN at that point. And Pleasence was like a plumber. You’d call him and he would do the job. A plumber doesn’t ask you what kind of toilet you have and how big your house is or if you live in a good neighborhood. You pay his fee and he comes by. And that’s how it worked with Pleasence. Benni also got us Palance. But Landau was different. His agent called us and asked us if we wanted to cast Landau in the picture.

Landau was doing a lot of horror movies at the time.

Palance and Landau were both at low points in their careers. Basically, if a film came along, they would take it. They had to support themselves. Between the time we made the deal with Palance, in the summer, and the time we were actually starting the film, in October, he had gotten hired to do a TV series, Ripley’s Believe it Or Not. He was supposed to travel around a lot for that. And Palance said: I don’t want to do your movie anymore. To Benni’s credit, he told Palance that if he tried to get out of the contract, he would sue him. Also, Palance hated night shooting and Benni promised him there would be no night shooting… in a movie called ALONE IN THE DARK! When he showed up on the set, he was not a happy guy. And he was pretty intimidating.

Danish poster for Alone in the Dark

Did he give you a hard time? You being a young director?

Yes and no. I’ve worked with actors who were really unpleasant. Palance could be difficult, but he was always nicer than he appeared. He had come in the day before his first scene and Bob had taken him out to lunch. So, at the end of my first day of shooting, which hadn’t gone particularly well, Bob said to me: Palance is really pissed off. He really doesn’t want to do this movie. We were walking down the street and someone recognized him and he nearly punched the guy! I hadn’t even filmed my first scenes with Donald Pleasence yet, for which I was a little concerned, because he was a great actor and I was a nobody. And I was supposed to meet Landau for dinner. So, I had a panic attack. I actually went into a liquor store and bought a fifth of bourbon, which I drank in the taxi cab to try to quell my anxiety. I thought: how am I going to deal with Palance? Then I said to myself: I’m the fucking director. Nobody’s gonna push me around!

The next day we were shooting the scenes on the grounds outside of the mental institution. It was actually two different places: the ward that they were locked up in, was an old hospital. But the exteriors were filmed at this beautiful mansion. And they had put Palance up in one of the rooms of this mansion, because they had no money for trailers. At lunch time, someone said: Mr. Palance is here and you should go talk to him. There are a few problems. I go up to see him and he’s in this huge room, all the way at the back, much like Mussolini, with the sun behind him. He didn’t seem particularly impressed to meet me. He wanted to talk about a scene we were supposed to film that afternoon, a dialogue scene with him and Dwight Schultz. And Palance said: I really can’t do that scene today. Nobody told me we were shooting that. I’m having trouble memorizing dialogue. And there was another scene, which takes place at night, where they escape. In the script Palance steals the car, drags the driver around and kills him. And Palance said: I don’t want to do that scene either, because I don’t want to kill anybody. I don’t like violence. Basically, everything we were supposed to shoot that day, he didn’t want to do. I said: Look, we have to do the dialogue scene. But we’ll do it as late in the day as possible, and if you want cue cards, we’ll give you cue cards. If you want to film it in little pieces, that is fine too. But we have to do it. As far as the scene tonight is concerned, let’s talk about it later. So we laid down the tracks for the dolly, and I told the crew to be on their best behavior. Palance came down to do the scene and he did it perfectly, all in one take. No cue cards. When it was done, I went up to him and said: Jack, that was fantastic! He turned to me and said: Meh, you’re full of shit.

An experienced director once told me that all actors are scared and insecure. I think he was right. Even with this shitty little movie, with a company and a director nobody had heard of, he was still nervous. He was relieved when he found out he came off well.

So, what happened with the scene at night?

During the dinner break I talked to him about that. He was a lot more relaxed by this point. Turned out he was an opera fan. Now, I was never big on opera, but I know a lot about classical music, so we had a conversation about that. Eventually, we started talking about the scene. And he said: Look, I really don’t want to kill the guy. And I said: Jack, it’s in the script. And he said: But why in the script do I have to kill the guy? I said: Because the audience needs to know that you are capable of murder. And he looked at me and said: They’ll know.

And he was right! It was one of the great lessons I learned during that movie. You don’t have to spell everything out for the audience. But still, I thought someone had to kill the guy in the scene. So Palance said: Have the fat guy do it. After that Palance and I had a good working relationship.

I thought he was absolutely fantastic in the film. I mean, that final scene… It’s one of the best things I ever did.

The final scene of Alone in the Dark

That last scene is awesome. It really serves as the punch line to the theme of everybody being crazy.

Yes, you see: I never had an interest in making horror films. I wanted to make art films. Those were the films I saw. Apart from Hitchcock, I mainly liked all the French directors of the time. So, I was secretly trying to do that. People always say ALONE IN THE DARK falls into the slasher category, but I disagree. It is a horror film, but I was also trying to make a statement about society. What’s normal and what isn’t? What if we break through the thin veneer of civilization? You have a bunch of people who are so-called crazy, and they’re out into the world and they fit right in. And also, what saves the family, is a moment of rationality on Hawkes’ part. He just says: Sorry, I guess I was wrong.

The movie holds up really well because of that extra layer, I think.

Yeah, people have started to appreciate the film more. It does really well when it’s played at festivals.

So, you didn’t have any ambition to become a horror director. Did you hesitate when Bob Shaye asked you to do the second NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET?

Yes. My initial feeling was to say no. My friend, who had produced my short film THE GARDEN PARTY, said: Don’t be an idiot! The movie is going to make a lot of money and you will have a career. That was good advice, because ALONE IN THE DARK didn’t do much business. It got me an agent, but they were more interested in me as a writer.

If A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET 2 hadn’t come along, I might have made another film or two, or I might have wound up being an editor. So I said yes. And we were off to the races.

I saw the documentary SCREAM, QUEEN: MY NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET about Mark Patton. You participated in that, of course. I was wondering if the finished documentary altered your perspective on your own movie.

Well, it’s been a journey. During production the idea of a gay subtext never came up. I never talked about it with people at New Line. I never had much time to work on the script. I don’t think I even talked to [screenwriter] Dave Chaskin about the script before we started filming. The script was the script. My job was to get it on film. Make it look good. Make it scary. It was an engineering kind of a job. I wasn’t going to question the blueprints.

When the film opened, expectations were not very high. At that time, a sequel to a horror film was just a way to squeeze a little bit more money out of it. New Line never expected it to make more money than the first one, but it did. It was the number one film that weekend. That is when the door opened for me and I went on to have a career. I was off to the next film and didn’t even think about it. But for Mark the clock stopped after ELM STREET.

None of the critics said anything about a gay subtext. And then the Village Voice comes out, and I get a call from the head of production at New Line, and she said: You won’t believe this review in the Village Voice, they call it the gayest horror film of all time. We had a laugh about that. I thought: Okay, if that’s the way you wanna see it, fine. After that I never thought about it again, until we had the thirtieth anniversary reunion. That’s when I did the interviews [for the documentary].

Mark seemed obsessed with the idea that Dave Chaskin had written this gay subtext. And I was like: Who cares? Get over it. I thought it was funny that this was the way the film was being interpreted.

Jack Sholder (middle) on the set of A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge. Photo courtesy of Jack Sholder

But what was the movie about in your view?

For me the movie was about repressed sexual angst that every teenager experiences. And yes, that angst can express itself in the question: Am I gay? Boys will call each other sissy or faggot. Now, if you are in fact gay, that is terrible to hear. Back then, being gay was a scary thing. My gay friends tell me that they used to think they were going to hell. It was extremely traumatic. So, I was aware of that context.

And yes, we did film a scene in a leather bar. I was living in the West Village at the time, which was the gay part of New York. Right after I moved to New York there was Stonewall. Gay life was out in the open, out on the street. I would see gay guys hanging outside clubs, smelling amyl nitrate. A lot of sex going on. That was part of where I lived. Of course, I had no profound understanding of what was going on. I just saw what was on the surface. And that was part of what’s in the film. Of course, AIDS had just come onto the scene and had changed everything. That was in the air at the time.

And the fact that Mark was gay… Maybe I should have guessed. But I wanted a good looking guy who could project vulnerability. In the first movie they had Johnny Depp whose features are almost feminine, very pretty. All the girls at New Line thought Mark was just as hot. So it never occurred to me he could be gay. And of course, he was in the closet. He was trying not to come across as gay. During filming, we had no personal relationship whatsoever. We had a good working relationship, very professional. But we never had lunch or dinner. He was in a kind of sour mood. And by the way: he had read the script and even he didn’t pick up on a gay subtext. It was one of the crew members who pointed it out to him.

So the crew was aware?

Yeah. People in the art department picked up on it. When Mark opens the closet in the movie, there’s a game called Probe. Somebody in the art department put it there as a joke.

Looking back on it, there were a whole bunch of decisions, starting with casting Mark that really… If you look at some of the exegeses as to why it’s the gayest horror film of all time, some of it is people reading stuff into things, some of it was intentional and some of it was stuff that people added that fed into that idea.

How do you look back on it now?

Well, it’s interesting. One of the actresses in the film asked me if her daughter, who was taking a course on horror films at UCLA, could interview me about A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET 2. We talked about a bunch of things. She send me her paper last night and there are a lot of interesting things in there. For instance, she notes that the use of the color red symbolizes Jesse’s personal hell. Well, actually, we were very conscious of the fact that the color red symbolizes Freddy, because whenever he’s around everything heats up. So, when you think of heat, you think of the color red. So heat and red represented Freddy. Now, if you want to say that Freddy represents Jesse’s repressed sexuality, then yes, you can make the jump from red to Freddy to repressed sexuality. But I didn’t consciously make that jump when I made the film. She also pointed to the poster, where Jesse is looking at himself in the mirror and sees this other inside of him, that’s frightening him. All of this makes sense.

When I was teaching, I would say: the director is a detective and the script is the scene of the crime. When someone has been murdered, the body is obvious. That is the plot. But then you start looking around, you find a hair under the rug. What does that mean? Every word in the script has a meaning. You have to pay attention. The job of the director is to connect all these things into a coherent story, and it’s always subject to more than one interpretation.

Did your students often ask you about A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET 2?

Rarely. I think it was almost off-limits for them to ask me about my career.

Mark Patton (left) in A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge

With THE HIDDEN you probably jumped at the chance to do something else than a horror film.

Right. After ELM STREET 2 I got offered about every horror script in Hollywood. Most of them terrible, some of them never got made. I really didn’t want to do another horror film. Things started slowing down, when the head of production of New Line, who I had known for a long time, called me and told me she had a script I might like. She was right. I loved it. It had a sly sense of humor. For me, the story was about what it meant to be human. Plus: I always wanted to do a cop movie, like Sidney Lumet. Even though it was a cop movie with aliens.

I think the reason it turned out so well, is that I had time to prep the film properly and I just knew what the film was supposed to be. I had this vision for it. All directors do a lot of preparation. Some do it by working on the script or the themes. I mostly do it by planning the movie meticulously. Shot by shot by shot. I have a list of every shot I need. Doesn’t mean I necessarily stick to it. But while I am planning every shot, I have to think about what the scene is about, why it is in the movie, how to best stage it, what the actor has to express to convey what the scene is about, where do I wanna put the camera. But even though I had planned it well, it was a very hard film to make.

What was hard about it specifically?

Well, my first three movies were all hard. ALONE IN THE DARK because it was my first feature, ELM STREET 2 because I had very little time to prepare and it had a lot of special effects, none of which I knew how to do, and then with THE HIDDEN I was afraid that I knew nothing about cops or shooting guns. Luckily, I had a very good DP who had also shot A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET 2. He was a great help. But Michael Nouri was very difficult to deal with. He was very insecure. He felt he should have had a bigger career than he did. He cost me an enormous amount of energy every day. He kept me off-balance.

THE HIDDEN shows you have a flair for action, especially car chases. The chase in this film is very good, and the one in RENEGADES is even better.

Yeah. The script opened with a big bank robbery and then the car chase. Bob Shaye said he didn’t want to do the robbery. We’ve all seen bank robberies before, right? And as far as the car chase goes, we’ve all seen that before, too. So, I said: I’m gonna make the best fucking car chase you’ve ever seen. But I really didn’t know how to do it. I asked my assistant to get me copies of all the car chase movies I could think of. The one I thought was the best, was THE FRENCH CONNECTION, because you always felt like you were in the middle of the action. The film that Walter Hill did, THE DRIVER, has a lot of car chases, but Walter likes to get way back on a telephotic lens. You’re looking at the chase from the outside. What I wanted to do was put the audience in the driver’s seat.

And unlike people who do horror poorly, who are only about the scares, I’m about the characters. How does this guy drive a car? This is a guy who can’t die. So, he’s gonna drive differently. That informed the way the chase was devised.

By the way, I should say that the first half of the chase was shot by the second unit. I storyboarded the whole chase and they went off and shot it. For logistical reasons they couldn’t stick to the whole storyboard, but the style I had pretty much made clear. I shot all the stuff with the actors in the car and the second half of the chase, when they’re coming up to the road block. It all came together in the editing.

When RENEGADES came along, I thought I had to outdo the chase I did in THE HIDDEN. I had a really good stunt coordinator. A guy called Mickey Gilbert. I asked him: is there anything you always wanted to do in a car chase that you never got to do? And there were two things: the moment where the car drives straight through the office and obliterates it. The other was a stunt where a car drives up a ramp, into a semi-truck and comes out the other end. We incorporated both of these. But the car chase was too long in the first cut. If it’s too long, you kind of get lulled into a rhythm. Then it stops being exciting, because you’ve seen too much of it. That’s what happened here. Originally, it was nine minutes long and we cut it back to seven.

One thing about my movies, the good ones and the less good ones, is they’re all well edited. They move along quickly. A lot of directors, if they have a 120 page script, their first cut is three and a half hours. If I do the same script, my first cut is a 110 minutes. I really like to keep things moving.

Jack Sholder (on the right, with hat), setting up a scene on the set of The Hidden. Photo courtesy of Jack Sholder

So, THE HIDDEN changed the way Hollywood perceived you as a director. Did the offer to direct RENEGADES come quickly?

No. THE HIDDEN didn’t make a lot of money. It tested through the roof, like it was gonna be a huge hit. Maybe it was the cast, I don’t know. But the movie never broke through. Everybody in Hollywood loved it. I was a hot director for about six months. But I wasn’t hot enough. I was a high B director, not an A or even an A minus. The thing is: you can’t make a great movie without a great script. You can make a good movie with an okay script. But that’s about it. So, I was angling to get that great script. One movie I really wanted to do, was GHOST. Couldn’t get there. Then things started to cool down and I knew I had to do a movie. RENEGADES came along. A buddy-cop movie. It had two hot young stars. Universal really wanted me. I didn’t ask them, they asked me. So I said: yes. It had action, humor, good characters.

For me, the film was kind of a disappointment. First of all, the buddy-cop thing is kind of clichéd. I thought I did a pretty good job, but it just didn’t click. I remember, it was in the spring and they were showing trailers of the upcoming summer movies, like the BATMAN sequel and a bunch of other high profile films. The audience is cheering and going crazy. Then they show the trailer for RENEGADES and it’s pretty quiet. At that point I knew I was in trouble. My career was going like this [moves his finger in an upward motion] and suddenly it went like this [moves his finger downward].

That’s when I did BY DAWN’S EARLY LIGHT for HBO, which was not as prestigious as it is these days. Now a top feature director will happily work for HBO. This was actually the film I always wanted to do. A grown up script about a serious subject matter. Great cast.

I was actually asked to do another film for HBO, It was an action-thriller that John Frankenheimer was supposed to direct, but the people at HBO said: You’re better at action than John Frankenheimer.

That’s a big compliment.

I’ll take the compliment, but John Frankenheimer is a great director and a master at action. But he was cool and I was hot at that point. I ended up not doing it.

Just to go back to RENEGADES for a bit. I wanted to read you a quote from a website called Outlaw Vern. Have you heard of it?

Outlaw Vern? No.

Outlaw Vern reviews movies, mostly action, in a funny but sincere way. Anyway, the quote goes: RENEGADES is a kick because you don’t really see this type of thing anymore, an action movie with a decent studio budget and a director with a bit of a nasty streak. Can you relate to that last bit, the nasty streak?

Let me see if I can get my wife to come on. But yeah, absolutely. Again, if you look at THE GARDEN PARTY, this is the director I wanted to be, as opposed to where fate has taken me. Wes Craven really expressed himself through the horror film, I expressed myself in spite of the horror film. In this way, I never think of myself as a horror film director. But in another way, I am. I’m perfectly suited to horror, because I have a twisted mind. Example: several years ago, during the winter, my wife got out of the car, closed the door, and unbeknownst to me, her coat was stuck in the door. I started to drive off. She was pulled over and almost run over by the car. She broke her pelvis. It was pretty horrible. She brings it up now and then, to make me feel bad [chuckles]. She was telling this story to other people, and she said I could have taken her head off. And something about the way she said it, struck me as funny. So I started to laugh. I didn’t want to, because it was a horrible event, but I just laughed. I reacted inappropriately. Horror films are also inappropriate.

Horror films are transgressive. And I have that transgressive personality. My wife and I were in a trattoria in Florence and there were a bunch of American kids sitting there eating, having a good time. They looked like high school kids, but there were several bottles of wine on the table. So, I walk over there and I say: Can I see your license? How old are you guys? And they all freaked out. And my wife is like: What are you doing? And I’m like: I’m just fucking with you guys. I thought it was the funniest thing. I usually find things funny that other people don’t find funny. And that sense of humor is in all my films.

Speaking about inappropriate laughter, what I found strangely funny in RENEGADES, is the scene where Jami Gertz’s character gets killed off. She’s just this sweet girl who’s along for the ride with these guys, and then – Bam! You just don’t expect her to get shot so violently in a film that is also quite lighthearted at times. I couldn’t help but chuckle at the audacity.

It’s interesting that you should bring that up, because when we filmed her dying, I thought it was a really powerful scene, with her life slipping away. I thought it was emotional. Then we screened it, and people laughed. I remember we had a big screening of THE HIDDEN at the Motion Picture Academy. The biggest venue you could find in LA, catered by Wolfgang Puck. Martin Landau was there. He and I had become friends and he was sort of a mentor to me. After the screening I was outside sooner than most people and Landau was with me. I had gotten a bad laugh and it bothered me. A laugh in a place that I thought was serious. And Marty asked me what was wrong, and I told him about the bad laugh. He said: I remember that laugh. It wasn’t a bad laugh. They laughed because they were uncomfortable. He was right. A lot of times, if an emotion is too big, if it doesn’t fit, that is what happens. Like with my wife, when she told the story of the accident, I didn’t laugh because it was funny. I laughed involuntarily, like a sneeze.

I would argue that in your time travel comedy, 12:01, the humor is mostly sweet instead of transgressive.

Yes. Actually, I would say that ALONE IN THE DARK, THE HIDDEN, BY DAWN’S EARLY LIGHT and 12:01 were my best films. And the last one, 12 DAYS OF TERROR, turned out pretty well. The rest in between: meh. I kind of like WISHMASTER 2.

I have to ask about a bad one, ARACHNID. You said earlier that you like to have a clear vision of what the film is supposed to be. Now, with THE HIDDEN, even if that special effect with the alien slug had not worked as well as it did, you would still have an awesome sci-fi action movie. But with ARACHNID, if the monster spider doesn’t work, you’re in trouble.

Yes. With ARACHNID, what happened was, I was supposed to do another movie, a twelve million dollar action movie with Steven Seagal. I had several encounters with Seagal. He is one of the worst human beings in Hollywood. Awful! While I was trying to get that movie together, they were asking me to do ARACHNID. It was a really stupid script. I was at a point in my career where I really couldn’t say no to anything that was for sure going to happen. And ARACHNID was for sure going to happen. I kept holding them off, in the hopes that we could finally get a green light for the Seagal movie. Every time it looked like it was going to happen, Seagal would do something to set us back. Finally, the ARACHNID people said: we have to go forward, so it’s either yes or no right now. At that point the Seagal movie basically fell apart. It never got made. He had agreed to do the film and then, after months of going back and forth, he suddenly thought the script was terrible. But he knew how to fix it. He wanted to rewrite it.

So, I agreed to do ARACHNID. Like I said, the script was really stupid. I thought I could work on it and make it halfway decent, but I discovered there wasn’t a whole lot I could do. But they paid me my fee and I got to live in Barcelona for six months. The people were great. The locations were great. Everything was great, except for the fact that I had to make a stupid movie. Part of my problem is I have good taste. If I get a good script, like THE HIDDEN, I can get really inspired, but if I get a really stupid script, I can only try to do my best. If I’m lacking that inspiration, it will never turn out as good.

They spent a lot of money on the spider. It was done by Steve Johnson in LA. I flew there to work with him on the design. When it was ready to be done, he was going to send over two people to help operate it, but he also said we were going to need six or eight more professional puppeteers. Each leg had to be operated by somebody, and there was the mouth and a lot of electronic stuff. And Steve also said his two guys were going to need a week with the six or eight puppeteers to figure out how to best work the spider. So, they got six university students who had no experience whatsoever. And they had like a day to figure out who’s moving what. It was like an invention no one has ever tried. The first day we used it, we only got two shots! And then there was one scene where the spider was supposed to be angry, and everybody just started making everything move frantically, like the spider was having a nervous breakdown. It looked like it was about to fly apart! By the end of the shoot, they finally figured out how to operate it.

When the shoot was done, I flew back to the States, while the editor was working on it. I don’t remember if they chose him or I did, but I don’t think the guy ever edited a horror film before. I came back to Barcelona to look at the first cut. Now, most directors will tell you that the first cut is always disappointing. You shot everything in the script, you have all the pieces, but still the cut doesn’t work. And it’s not a rough cut either. It’s not like the editor just throws it together. He or she cuts it the best way possible. In this case, it was a giant spider movie without a giant spider. The spider didn’t work at all. It was just like a lump. I ended up using every trick and skill I had ever learned as an editor to fix it. Every working shot of the spider we used multiple times. We would speed it up, blow it up, run it in reverse. Sometimes the close-ups of the spider were so tight, you couldn’t even see it was in a completely different place.

It’s the only film I’ve done that I think is a real dud. I’ve had people tell me that they like it, but it doesn’t change my opinion.

On the set of Alone in the Dark. From left to right: Bob Shaye, Erland van Lidth de Jeude, Martin Landau, Jack sholder and Jack Palance. Photo courtesy of Jack Sholder

Related talks

Special thanks to Jack Sholder for providing us with the set photos used in this article.

This interview first appeared in a shorter version in the Dutch fanzine Schokkend Nieuws. Above is the full version of this talk, edited only for clarity.