FUCK THE BONUS

GARY SHERMAN

Gary Sherman, photo by Mari Mur

Out of the six theatrical features Gary Sherman made in the seventies and eighties, three are bona fide classics: DEATH LINE, DEAD & BURIED and the psycho-pimp-on-the-loose thriller VICE SQUAD. That’s not a bad tally. In December 2020, speaking from his house in Michigan, Sherman told Roel Haanen the story of his career, and the series of circumstances, which include singing with Bo Diddley, protesting the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968 and working with Jonathan Demme in London, that led to him becoming a filmmaker.

I read that, before you became a filmmaker, you were a musician for Chess Records at a really young age. Were your parents in the music business?

No, my dad was in men’s haberdashery. You know, men’s clothing and accessories. He was a manufacturer and retailer. He was quite successful. He died at the age of 102 and danced all to way to the grave. Never sick a day in his life.

What made him successful in what he did?

Before the war he was big into silk, but when there was no more silk during World War II, he went bankrupt. After the war, the price of silk had gone up tenfold or twentyfold, because all the silk was destroyed. It all came from Japan. My dad, who knew fabric inside and out, figured out how to make a tie that was silk on the outside and synthetic fabric on the inside. That way he could make a silk tie for a fraction of the price. He invented the one dollar silk necktie, which became the rage all across the United States. He went from being bankrupt to being extremely successful.

Did he want you to become his successor in the business?

Absolutely. First he went after my older brother, but Mark wanted nothing to do with it. Then he came after me. But I said: Dad, that’s not what I want to do. And I went off to art school, to his chagrin. I left home and put myself through art school. We were separated for a while.

Because you decided to go to art school?

Yeah, and because of my lifestyle. I was a hippie. It was the sixties, man. My dad’s politics were quite left, but my mom’s weren’t. But my politics were even further left of my dad’s. I got married after college and my mother wouldn’t come to the wedding unless I got a haircut.

Did you?

Yeah. My dad and my bride to be talked me into it. I didn’t really care if she came or not. My mother and I were always… My mother died almost twenty years before my dad, which gave me a chance to become close to him. My dad was quite a guy. My mother always kept us a bit separate. The last ten years of his life I got to know him really well. I moved back to Chicago to spend time with him.

When you went to art school, did you already have the ambition to become a filmmaker?

No, my whole life, from about age six or seven, I was an artist in search of a medium. I wrote cartoons when I was really little. They were published in school. When I was a kid my parents were all in favor of me studying art. At age eight I went to the Saturday school of SAIC, which is the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. One of the best art schools in the world. They had a junior school, which I attended all the way through high school. I drew, I painted, I sculpted. But when it came to college, and I wanted to go to SAIC, my parents said: No, you have to become a doctor, a lawyer or an engineer. As a Jewish kid, that’s all you’re allowed to do. [Laughs]

So, you put yourself through art school?

Later on, yes. I had told my parents I wanted to attend the Illinois Institute of Technology to become an engineer. I was also accepted at MIT and Caltech, so I explained to my parents that I wanted to go to IIT because I didn’t want to leave Chicago. The real reason was that IIT also had the Institute of Design, which was set up by Moholy-Nagy and Mies van der Rohe of the Bauhaus. After Hitler had classified all of them as degenerate, they had a choice of leaving Germany or going to a concentration camp. They came to Chicago and set up the Institute of Design at IIT. Mies designed Crown Hall on the campus, which is now one of his most famous buildings. Crown Hall housed the Institute of Design. The ground floor was for architects, the basement for designers. Mies liked architects better. [Laughs] So, after about a year, my parents discovered that while I was at IIT, I was not enrolled at IIT, I was enrolled at the Institute of Design. That’s when I left home. I moved into a little room above a garage in a terrible neighborhood. It had no heat. But it was all I could afford.

What medium were you leaning towards at that time as an art student?

The first year was foundation year. You had to learn every form of design. Moholy-Nagy didn’t believe in teachers. He felt that teachers were always teaching history. So, anyone who taught there, was only allowed to teach one day of the week. The rest they had to be working. The people we had coming in were unbelievable. Mies came every week. [György] Kepes came. Cosmo Kampoli taught sculpture. Misch Kohn would come and lecture us on print making. An incredible environment. Aaron Siskind, the father of modern photography, came in to critique our work. Siskind was a little guy, always covered in cigarette ashes. He lit his first Pall Mall in the morning and with that cigarette he would light the next one and so on, all day long. Anyway, he saw my work and asked me what I wanted to do. I answered: either visual design or product design. He said: No, you’re a photographer. I take three students a year and you’re one of them. Next thing I knew I was a photography major.

So how did that lead to film?

Well, this is where Chess Records comes in. I was working my way through school and one of the things I did to make money was play in a band. We played record hops on weekends. We decided we wanted to put out a record, so we recorded one at the Chess studio. Afterwards, the sound engineer, a guy called Ron Malo, came up to me and asked if I could read music. I said I could. He said I had an incredible range and offered me studio work at Chess, mainly singing backing vocals. To which I said yes immediately. I was the white kid at Chess. There were only two other white musicians. One was a guitar player whose name I don’t remember, the other was Charlie Musselwhite. They were established musicians, I was just the white kid. It was great. I got to know every one of those guys: Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, Gene Barge.

Around that same time I found an old 16mm Arriflex camera in school. Nobody knew anything about it. So, with some help I took it apart and got it to work. I started shooting some footage, just for fun. And when Aaron Siskind gave us an assignment to photograph people at work, I asked him if I could shoot it on the movie camera. Aaron said: Fine, as long as it’s good.

I was booked on a session with Bo Diddley, singing background on We’re Gonna Get Married. He was really friendly with me. So, I asked him if I could film the rest of the recording. He said: Yeah, man. I love having my picture taken. So, I’m in the studio shooting my stuff when Marshall Chess, who’s Lenny Chess’s son, asked me what I was doing. I told him it was for school. He really wanted to see the footage when it was done, so a few days later I’m taking this 16mm projector and all my cans over to his office and I throw it up on the wall for him. After a few minutes he says: This is great. He gets his dad and his uncle and some of the A&R guys. I run it again and everybody’s going: Wow, this stuff is great. Well, it was pretty far-out footage. So, Marshall says: Let’s make a movie! I said: I don’t know how to make a movie. He said: You do what you do and I’ll hire a crew. Bo was about to go on tour and they wanted me to go with him. I asked school if I could get that time off. So, I went on tour with Bo Diddley and shot the footage. When I came back, Marshall put me in contact with a post-production house and they taught me how to edit it. I ended up putting it together and Marshall sold it to like seventy-five television stations around the world. It won a bunch of awards and suddenly I was a filmmaker.

And you were eighteen or nineteen at this point?

Yeah, I was nineteen when the film was finished. I used to lie about my age, because who would hire a kid? Right after the Bo Diddley film, I got calls from other record labels who wanted me to do these music performance films, which were basically music videos before they were called that. I did one for a flower power band called The Seeds and I made it really psychedelic. In the sixties you had these solarized photos, which is basically half negative and half positive. You get that effect when you flash the film while developing. I knew how to do it in still photography, but I thought: Boy, I bet I can also do that with motion picture film. So, I printed my negative on print stock and I developed it by hand. In the middle of it I flashed it. Then I used that as negative, so that negative would print as positive and the positive as negative. I put it together on an optical printer. No one had seen solarized film before. That got shown all over the place.

And then Dale Landsman, who was the creative director at Needham, Harper & Steers, which was a big ad agency, had seen the Bo Diddley film and the thing I did for The Seeds. He contacted me and pretty soon I was shooting advertising films and commercials for them.

Donald Pleasence and Norman Rossington in Death Line

So, how did you make the transition to feature films?

Well, 1968 happened. The Democratic National Convention.

You were at the protest?

Not only was I there, I was part of the organization. I was involved with a group called the Urban Training Center. I was very radical. We managed to get ourselves in a lot of trouble. By the end of the convention I didn’t like America anymore. They used the anti-war movement to crush the civil rights movement. I said: Fuck this! I don’t wanna be here anymore. My mother was British. I had family there. I was already married by this point, so Carol and I went. I was granted working papers immediately. I was doing commercials in London and my producing partner, who was Jonathan Demme, kept telling me I should make a movie.

What was your relation with Demme?

He was my best friend at the time. We were together every day, all day long. He produced and sold what I made. Together we wrote a couple of screenplays. Basically, they were crap. We were kids and we were writing student films. Very political stuff, but preaching to the converted, you know? We were writing and writing and selling nothing. At one point, John Daly of Hemdale Film said: You’re a good writer. Why don’t you write something somebody would want to make? And I asked him: What would that be? And he said: I bet you could write an amazing horror movie. And I walked away from that thinking: Wow, horror might be perfect to hide a political polemic in!

So what were some of the political ideas that informed DEATH LINE?

I had been bothered by British classism. I was living in Hendon at the time and I had to take the tube from Golder’s Green to the West End every day. I read up on how it was built. I read about the navvies, miners from Scotland and Wales, who were brought to London to dig the tunnels, and how they were mistreated. When there was a cave in, they didn’t dig them out. Because why spend money on working class people? Then there was another story I heard while I was in England, which was the legend of Sawney Bean. He was a highwayman whose family turned to cannibalism. They couldn’t buy food anymore, because someone would turn them in. So that all came together in DEATH LINE. Here’s a bunch of people who were left for dead because they were working class. They turned to cannibalism to survive. Mostly they ate tube workers and passengers, who were working class as well, so nobody cared. So that’s how the idea started.

How many people picked up on that commentary on the British class system?

Actually, no one but Jay Kanter. It took Paul Maslansky more than twenty years to realize that he had produced a political horror film! The critics knew it though. Robin Wood got it from day one. He became my champion. Aside from Jay Kanter and Alan Ladd Jr., who allowed me to make DEATH LINE, if I have to credit anyone with my career, it’s Robin Wood. He loved my work.

How different was it for you to make a feature as opposed to commercial short films?

A lot different! Aside from the music films I had done, most of my commercial films were thirty seconds. I was like twenty-four years old and here I am directing Donald Pleasence and Norman Rossington. Between the two of them, they’d been in more films together than I had seen in my whole life.

Hugh Armstrong as The Man in Death Line

And you had Christopher Lee.

Yes. He called Paul [Maslansky] and said: I hear you’re doing a film with Donald Pleasence. How come I didn’t get an offer? And Paul said: Christopher, you cost more than our whole movie. And then Lee said: I would kill to have a one-on-one scene with Donald Pleasence. If you give me such a scene, and I don’t have to wear fangs, I’ll do it for scale. Because back then, Donald was the actor’s actor. He had just won a Tony for The Man in the Glass Booth on Broadway. Every actor wanted to work with him. This was long before he started doing low budget horror films for money. He had gotten married too many times. He took paying alimony seriously. He had children with these women and really felt it was his duty to take care of them. And he did. He worked his ass off to make money.

I read that Marlon Brando was seriously considering taking the role of the cannibal. What’s the story on that?

Jay Kanter, who financed the movie, was Marlon Brando’s first agent. Jay knew that Marlon wanted to do a movie where he had so much makeup on his face, no one would know it was him. At the time he was doing LAST TANGO IN PARIS. We talked and he really wanted to do it. He was all set. And then his son Christian, who was a teenager at the time, got pneumonia and nearly died. So, Marlon rushed through the ending of LAST TANGO and flew home to take care of his son. We knew he wasn’t coming back. Before Marlon’s name was even mentioned, I had already met Hugh Armstrong for the part. I have no regrets, because he’s fantastic.

The film is quite gruesome, especially for its time. Did it get you in trouble with the British censors?

We knew we would have trouble with [John] Trevelyan and his gang [the BBFC]. We just put some stuff in the film that we didn’t mind losing. We knew we had to make some concessions. But we got an X anyway, which wasn’t so bad at the time. It certainly didn’t hurt us. The distributor, which was Rank, was more concerned about it. They put us on the second half of a double bill with a movie called NIGHT HAIR CHILD, but by the second night there were lines around the block of people wanting to see DEATH LINE. Most theaters dropped NIGHT HAIR CHILD and doubled the number of screenings of DEATH LINE. It was funny, because the double bill poster was cut diagonally, so when theaters started dropping NIGHT HAIR CHILD the poster of DEATH LINE suddenly became a trapezoidal poster. You can still find those on eBay.

After DEATH LINE it took a while for you to make a second feature. What happened?

AIP is what happened. DEATH LINE was a huge hit in Europe. But it was sold out from under us by the financiers in some cross-collateralization. It was bullshit. AIP cut the picture to shit and called it RAW MEAT and released with an advertising campaign that had nothing to do with the movie. They even redubbed parts of it! Robin Wood wrote a piece on that called Butchered, in which he warned people not to go see RAW MEAT. Samuel Z. Arkoff wanted me to work for AIP and I told him there was no way I would ever consider working for him or his company. RAW MEAT died a terrible death in the United States. I thought: I’ll just keep making commercials. They’ve been very good to me.

But Jay and Laddie [Alan Ladd Jr.] kept pushing me to come back to the States. Jay kept inviting me to Los Angeles to do stuff for First Artists. They were trying to set up a television division and Jay thought I was the perfect person to get it going. We never got anything off the ground, but I met a lot of people in television. I started getting some offers.

Is that when you made MYSTERIOUS TWO?

Yeah. It was made in 1978. Between ’72 en ’78 I continued doing commercials, mostly in Europe. I did a few in the States and that’s when the television stuff happened. I wrote a couple of things for Jay, who was now at Fox, I wrote something for Elliott Kastner at Paramount. But I wasn’t all that eager to go back to directing features, because they take so much time. Truth is, I was making too much money doing commercials. But a television movie was nothing. That didn’t take the same amount of time. So I did MYSTERIOUS TWO.

Was that based on an actual couple called He and She who claimed to be in contact with UFO’s?

Yes, I was following the stories about this couple called He and She who were going around the country recruiting people to go with them to outer space. And then they suddenly disappeared. I thought: This is interesting, maybe they went! Based on what I read about them I wrote this fictional version called MYSTERIOUS TWO. Actually, when we were developing it, Deanne Barkley, who was heading the movie division at NBC and who had been a big fan of DEATH LINE, thought it could become a series. So, it was cast like a series. Fred Silverman, who was president of NBC, liked it as well and wanted to do it as one of the Sunday night big events. So, we made it, but I think it was too far-out. The producer, Alan Landsburg, said: Nobody’s going to understand this fucking thing! They didn’t know what to do with it. By this time Deanne had left the network, so I had no rabbi for the movie anymore. Fred Silverman had left as well. Landsburg just didn’t get the movie. He re-cut it and added some footage. It took a couple of years before the network finally put it on the air.

What did he change?

He added that whole prologue with the rockets. Originally the movie starts with the guy playing the flute. He also shot some footage giving the audience a look inside the tower, which I absolutely did not want. I wanted it to be as abstract as possible.

In this period you also wrote PHOBIA, right?

No, I had already written that in England. When I was in England, my friend and I wrote a whole bunch of scripts that we sold, to Hammer and others. Some of them were eventually made, but they don’t have our names on them. I always thought I would someday make PHOBIA myself. What I liked about it, was that it was two separate stories that come crashing together in the end. But they ended up only shooting one of the two stories.

How did it get made?

I‘m at home one day and there’s a knock on the door. There’s this little guy at my door who says: Hi! I’m Ron Shusett and I’m going to be the biggest producer in Hollywood and I wanna work with you. Apparently, he loved DEATH LINE and had gotten my address through a mutual friend. He asked me what scripts I could sell him. He had a pile of scripts of his own that he asked me to read. The one script that I still had was PHOBIA. When I sold the script and heard that John Huston was going to direct it, it was the most exciting thing that ever happened to me. I couldn’t go to the set, because I was working when they were shooting it, so I never got to meet Huston. And then when I saw it, I was so disappointed. It was the greatest piece of shit I had ever seen!

Was DEAD & BURIED one of the scripts that Shusett brought to you that day?

Yeah, it was in that pile. We started talking about it. I liked about two thirds of it.

Was there a specific act that you didn’t like?

No, there was a lot of mumbo-jumbo in the script about how exactly Dobbs resurrects the bodies. We didn’t need that. The interesting thing is that he does it, not how he does it. The more you try to explain, the more people will say: Bullshit! Ron agreed with me, but Dan O’Bannon did not. So he separated himself from the film. At first we weren’t able to get a deal on DEAD & BURIED, but then the Saturday after ALIEN opened, Ron called me and said: I think we can get DEAD & BURIED made now. Within three weeks we had a deal.

The movie holds up really well. It’s got some of the creepiest scenes that ever came out of eighties horror.

Thank you. In 2021 the movie is exactly forty years old. We’re doing a 4K Blu-ray that will be out in the spring. It will feature some stuff that we had to cut out in 1981 to get a rating. We’ve put it back in now. People have never seen this version. It’s almost the version I originally made. Some of the footage we could not find.

Oh, and then I get a call from Joe Renzetti, who did the score of DEAD & BURIED, and he tells me that this record company wants to do a vinyl record of the soundtrack. So, simultaneously with the Blu-ray the vinyl will be released.

How much footage did you put back in?

It’s not a whole lot. It’s only seconds of gory shots and context that we had to edit out to appease the ratings board.

DEAD & BURIED is also one of your best looking films.

Absolutely. I had Steve Poster as a DP, who would later work with Ridley Scott on SOMEONE TO WATCH OVER ME. I knew Steve since we were kids. I thought he was a major talent. He had done some television stuff that I thought was terrific. I wanted him to shoot DEAD & BURIED, but the studio wanted somebody with experience as a DP on a feature, which Steve did not have. Then I heard that my buddy Jeff Bloom, who was doing a horror movie called BLOOD BEACH, had lost his DP. I called Jeff and told him I wanted to hire Steve, but they wouldn’t let me until Steve had done a feature. Jeff looked at Steve’s stuff, liked what he saw and hired him. Frank Capra Jr., who was the head of production at Avco Embassy at the time, called the production manager of BLOOD BEACH and asked to see dailies and production reports. By the second week he approved of Steve to do DEAD & BURIED. Steve has seen the 4K footage and says it looks pristine.

Heather O’Rourke and Nathan Davis in Poltergeist III

Your movies always make the most of locations. The London tube in DEATH LINE, the New England fishing town in DEAD & BURIED, the Hollywood streets in VICE SQUAD. When you envisioned a poltergeist story in a newly built high-rise in POLTERGEIST III, what were some of the ideas that led to that?

Jay Kanter and Laddie were running MGM at the time. They wanted to do a third POLTERGEIST. They asked me if I would do it. I had no interest in doing a sequel. I always like to have some sort of polemic buried in the film, but I couldn’t see any way of doing that with POLTERGEIST III. Even DEAD & BURIED is clearly an allegory. It’s not meant to be taken literally. So, I declined, but they kept coming back to me. They needed someone whom they could trust to keep it under control, because the second POLTERGEIST had gone way over budget. Jay and Laddie said: We let you make DEATH LINE, we gave you a career, you owe us. So I relented, but I had conditions. First: I wanted to shoot in Chicago. Second: I wanted to shoot in the John Hancock building, because that was something I always wanted to do. It’s been such an important building in my life. It was designed by students of Mies. I had previously written a caper film that took place in the Hancock building, but that never got made. So this was my chance. And third: I wanted to do all the effects practical. Because I knew it could be the last big budget studio horror movie without any CGI. Which would be poetic, as I was also one of the first to use a computer effect in a movie as well, in MYSTERIOUS TWO.

That light cube where He and She emerge from?

Yes, that was done with a computer. It was done before hardly anyone thought of using computers. I worked with a guy called Wyndham Hannaway in Boulder, Colorado. He did medical imaging. He was one of the first early experimenters with digital image. I told him what I wanted to do and he got all excited about it. We used the Cray computer at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, which he had access to. At the time it was the most powerful computer in the world. It was huge. It was built into a bunker in the Flatiron Mountains and it went on forever. It looked like a set from 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY. Actually, it was used as a movie set in Woody Allen’s SLEEPER. We used an electron gun stimulator on microfilm to create the line images. We shot one electron at the time, so it took us an hour to do one frame. Then I transferred the microfilm on an optical printer to Kodalith to create the line images. From that I made the negatives and positives. On optical printers I created all the traveling mattes and I used pieces of glass to use as diffusers. It’s only a moment in the film, but at the time it was pretty amazing. But nobody knew it was a computer effect, because I never told anyone.

Did MGM try to persuade you to use digital effects instead of practical on POLTERGEIST III?

Well, Laddie asked me what it would cost to do the whole film practical. And I told him: exactly the same, because the shooting schedule would be longer, but the post production wouldn’t cost a penny. Because there isn’t even a dissolve in the movie.

Those are the saving graces of the movie: the location and the effects.

That’s the whole movie to me. I hate the script. There was this whole ending I wanted to do, which they didn’t want because it was too expensive. So we did an alternate ending that was awful. We previewed the film and they said: Okay, shoot the original ending. We’ll give you the extra money. We were getting ready to shoot that and then Heather [O’Rourke] died. I wrote a third ending, which is the one that’s in the film. We had to shoot that with a double for Heather. I didn’t want to finish that movie, but I didn’t have a choice. The board of MGM said: you either do it or we’ll get somebody else. I’m glad I finished it, but I hated doing it. It’s still hard for me to watch that film.

Richard Fire (left), Gary Sherman and Heather O’Rourke on the set of Poltergeist III

Let me ask you something about VICE SQUAD and WANTED: DEAD OR ALIVE. A lot of horror directors from the seventies and eighties were pigeonholed in the genre and tried to get away from it. Were you also consciously trying to move away from horror?

I love horror. Love writing it and watching it. But back in those days there was no respect given to horror films. The fact that Samuel Z. Arkoff could come in and cut the shit out of DEATH LINE, which ended up becoming a classic film in its original form, and make it into a piece of crap, that about says it all. Fortunately, nobody can see Arkoff’s version, because it hasn’t survived in any form. The prints were all shitty Kodak prints which have long since gone red, if they even exist anymore. Today, you can only see my version, which is good. But it really destroyed me. If Ron Shusett hadn’t come along I probably wouldn’t have made another horror feature.

As for VICE SQUAD: I had done DEAD & BURIED for Avco Embassy and Bob Rehme, who was the president of that company and a real stand up guy, says: I wanna make another movie with you. He puts a stack of scripts on his desk and says: Pick one. You can rewrite it, do whatever you want, you make it. One of those was VICE SQUAD. I have to admit, the original script was dreadful. It was written by the police officer who had experienced these things. He didn’t know how to write. But everyone liked the idea.

The girlfriend I was living with at the time was working as an executive at Warner Brothers. We used to read scripts in bed at night. She was reading 9½ WEEKS and I was reading VICE SQUAD. She wanted me to read hers and I wanted her to read mine. And she read VICE SQUAD and said: This is terrible! You can’t make this movie. And I said: But I can rewrite it and make it into something special. It all took place during one night and it’s all a chase. She thought I should do something more elevated and told me to pass on it. I told her it was going to be a hit. Anyway, she ended up passing on 9½ WEEKS and I went to Bob Rehme and said I would do VICE QUAD if I could do a page one rewrite. He said: Go for it!

But I didn’t get away from horror doing VICE SQUAD. Because a lot of reviewers commented on how the movie created a great movie monster, in the character of Ramrod.

It is one hell of a character. A truly despicable human being.

Yes, I wanted him to have no redeeming qualities. I wanted you to walk away from that movie feeling disgusted with the whole sex-for-money industry and the exploitation of women. It worked for a lot of people, but not everyone. I was about to do a movie at Paramount for John Milius, and he showed VICE SQUAD to [vice president of production] Dawn Steel. She said: Not only wouldn’t I hire this guy to do anything, I wouldn’t even want to meet someone who’s that misogynistic. And Martin Scorsese, who was dating her at the time, said: Are you crazy? This is one of the great films of the year. This film should win the Oscar for best picture, but nobody has the balls to even nominate it for anything. They got into a big fight about it at a dinner party. They were screaming at each other. I lost the John Milius picture, which was UNCOMMON VALOR, but eventually Dawn came around and decided that she liked me.

Wings Hauser as Ramrod in Vice Squad

Whose idea was it to have Wings Hauser sing that song Neon Slime?

That was my idea. I had met Wings on the set of DEAD & BURIED and we used to sing together. Wings was married to Nancy Locke who played a role in the movie. Wings came up with her, together with the kids. They were up in Mendocino for quite a while. Wings and I became friends, we played guitar together and sang songs. He was one of the stars of a soap opera called The Young and the Restless in which he played Greg Foster, the world’s nicest person. Now, singing with Wings, talking with Wings and getting drunk with Wings, I realized there was an anger that was bursting to get out. When I was writing VICE SQUAD I asked him if he’d be interested in playing Ramrod. And he said: I’m not sure. I don’t know how much of that anger I want to get in touch with. We worked on the role together and finally he said: You know what? I can do this. So, I brought it up with Bob Rehme and he thought I was crazy. He said: You want Greg Foster, the world’s nicest person, to play Ramrod? No way! But I brought Wings in to read for them. We rehearsed what we were going to do at the audition. So, Wings comes in as Ramrod, looks at the executives behind the table and says: Which one of you motherfuckers thinks I can’t play this part? He zeroes in on Bob Rehme, grabs him by the tie and pulls him in close and whispers: You think I’m not evil enough to play this fucking part? And Rehme says: Not anymore. That’s how Wings became Ramrod.

For someone like me, who has never seen The Young and the Restless, it’s almost unbelievable that Wings Hauser was once considered a typical nice guy actor. My first introduction to him was Ramrod.

Wings claims I ruined his life, because after VICE SQUAD everyone saw him as a villain and he doesn’t want to play villains. Walter Hill called me to ask about Wings, because he was thinking of casting him in a movie. Two weeks later Walter calls me back and tells me that Wings turned him down. I call Wings and ask him if he’s nuts, turning down a Walter Hill movie. And Wings says: I don’t wanna do that anymore. You made me get in touch with that person and I don’t want to deal with him anymore. When we were shooting VICE SQUAD, we used to wrap around five a clock in the morning and I had to take him drinking, get him drunk. He didn’t want to go home as Ramrod. I think he was afraid that that person really was part of him. Wings wanted to be the romantic lead, the good guy, and his career went no place, unfortunately. But he’s unbelievably talented.

VICE SQUAD was also the start of a whole series of movies about pimps and prostitutes, like the ANGEL movies, STREETWALKIN’ and STREET SMART.

Walter Hill even credits VICE SQUAD for the way 48 HRS. is filmed. Edgar Wright thanked me publically for inspiring him to do BABY DRIVER.

Lydia Lei and Season Hubley in Vice Squad

How was working with Rutger Hauer on WANTED: DEAD OR ALIVE?

I loved working with him. We spent an inordinate amount of time together. He was such a perfectionist. He demanded perfection out of himself and everyone around him. I never had a harder job than directing him, because he was so demanding. But that was really great. His performance was perfect. Sadly, it wasn’t the greatest script. We only had two weeks to write it.

How come you only had two weeks?

Again, the name Bob Rehme comes up. He had just left Avco Embassy and gone to New World. He called me up and said he needed a favor. He had bought the title WANTED: DEAD OR ALIVE and had a script written, which he said was abysmal. But the movie was already booked into theaters because of the title. They sold it on the title alone. He sent me the script and asked me if I could work on it. I said: The only thing you can do with this script is throw it in the garbage can and start over. Bob said: Great, go write a new script! But I couldn’t do it by myself in just two weeks, I needed another writer. Denise Di Novi, who later became a big producer, was Bob’s assistant at the time and she recommended Brian Taggart. I met him and thought he was amazing. The next day we were put into an office together and we wrote for two weeks, day and night. Even in preproduction we kept writing. We didn’t know where we wanted to go with the ending, until I thought of that scene with the hand grenade. When we came up with Fuck the bonus, we were jumping up and down on the couch, screaming, Fuck the bonus! Fuck the bonus! Our producer Arthur Sarkissian came in and asked us what was going on. We told him about the scene and suddenly he goes screaming around the office: Fuck the bonus! We all thought Fuck the bonus would become bigger than Make my day, but that didn’t happen.

You said earlier that all of your films have some sort of polemic hidden inside them. What were your intentions with WANTED: DEAD OR ALIVE in that respect?

WANTED: DEAD OR ALIVE reflected my hatred of terrorism. I don’t care who the terrorist is or what his reasons are, there’s just no reason to kill innocent people. I lived in England during the IRA terrorism. My wife and daughter were inside Harrods when a bomb went off. They weren’t hurt. There were three or four bombs that went off within a few blocks of our house. Even though I agree with the IRA about their goals, I could never support them because they resorted to violence. Unfortunately, a lot of people thought of WANTED: DEAD OR ALIVE as an anti-Arab film, but it was anti-terrorism.

Actually, I blame Roger Ebert. He was the first critic to write that this movie was anti-Arab. It spread like wild fire. I got into a real argument about it with him, but he had already published it. Eventually I convinced him that it wasn’t anti-Arab, but he was not going to write a retraction.

I was very upset by the fact that people thought it was something that it really wasn’t. I don’t have those feelings about Arabs or people from the Middle-East. Even though I’m Jewish, I hate how the Israelis treat the Palestinians. I agree with a lot of what the Palestinians want. I just cannot agree with terrorism. Malak was like Ramrod to me: an evil fucking person. In retrospect I probably should have done it differently, maybe put a very sympathetic Arab character in the films as well. Which I tried to do with the girl who wants to stop him at one point. He shoots her in the face. I thought that shows he has no qualms about killing his own people. He doesn’t represent anyone or anything, he’s just evil. But it didn’t come through.

Speaking of Roger Ebert, he was also rather dismissive of LISA. He wrote in his review that it was all climax and no foreplay, which made me wonder if we had seen the same movie. I think LISA is rather subtle in the way it builds up the tension.

I don’t know what it was with Roger. He didn’t like any of my films. We had a mutually close friend, so we knew each other, but we just had this ongoing thing. He wrote in an article: Gary Sherman is a really good director. Why doesn’t he pick some decent material? He kept throwing that kind of thing at me, although I didn’t know what he wanted me to make. I always wanted to make films for an audience, not for myself. Roger never understood that.

Rutger Hauer and Gene Simmons in Wanted: Dead or Alive

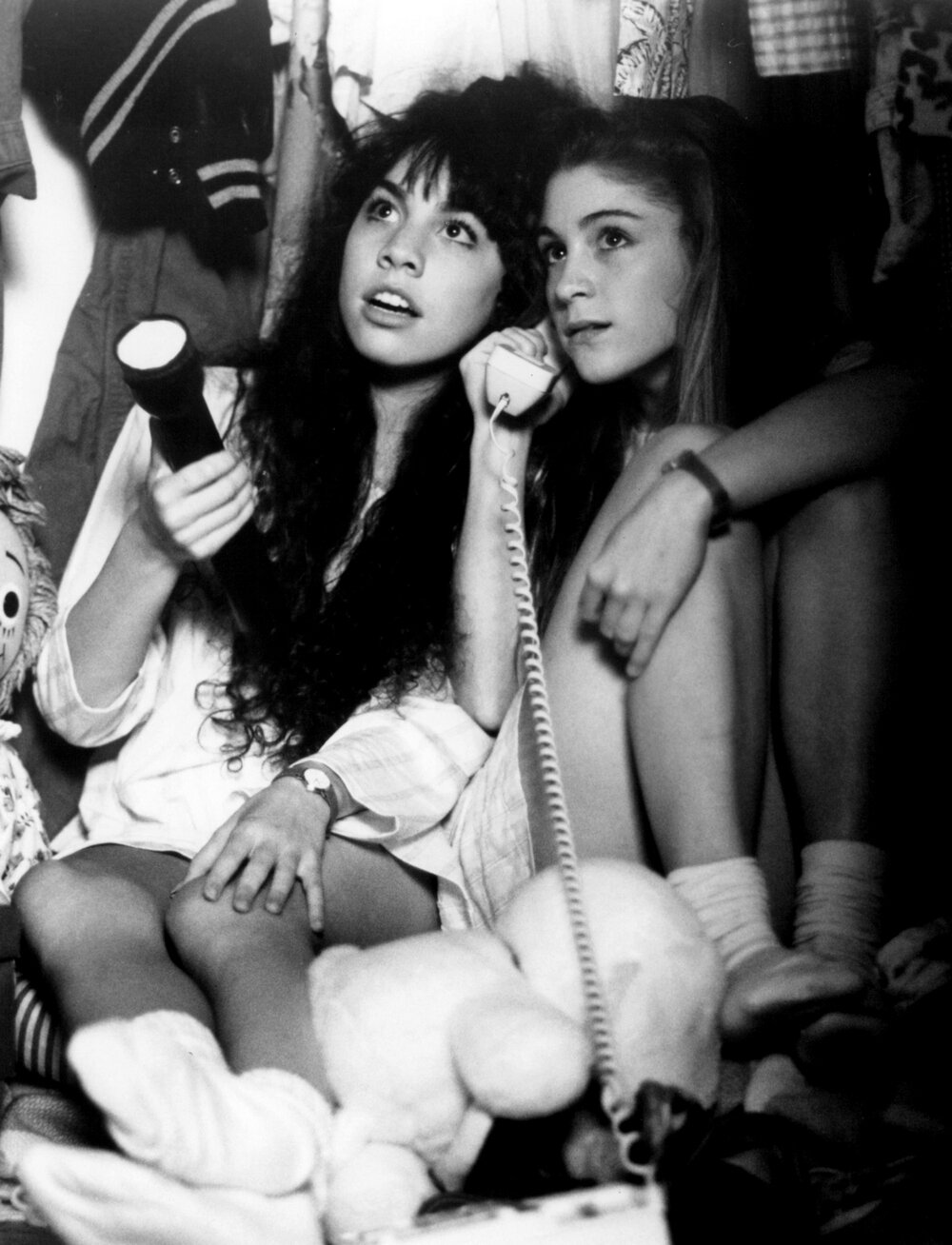

One of the things I like about LISA, is how the sleazy movie that it could have been, stays lurking beneath the surface. It’s like one of those erotic thrillers of the eighties, but with a teenage girl. It makes the movie somewhat of a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

Yeah, it was a psychosexual thriller with all the intimacy. But there were a few problems with it. They have to do with how it was made, but that’s a long story.

I’d like to hear it.

Okay. Richard Berger at MGM wanted to thank me for finishing POLTERGEIST III and told me to bring him a script that I wanted to make. I had written LISA for my daughter. She was a teenager at the time and she was always telling me how she couldn’t watch any of my films, because they were all R or X rated. So I wrote a script for teenage girls. Her mother and I split up when she was quite young, so my daughter grew up with a single mom. LISA was about that.

I bring it to MGM and they’re all excited about it. Frank Yablans wanted to produce it with me. It started moving forward, with a budget of seventeen million dollars. I was going to shoot it in Chicago. We were scouting for locations when I get a call from Dick Berger telling us that MGM just went into bankruptcy. Now, Frank takes the script to Dawn Steel at Warner Brothers and she loves it. Warner tried to buy it from MGM, but because LISA was a named asset in the bankruptcy, MGM was prohibited from selling it. It looked like it wasn’t going to be made.

Then Frank asked me if we could make LISA for five million dollars, instead of seventeen. He said: MGM can’t afford seventeen million production money, but they can afford five million in a negative pickup. So we asked Berger and he said: Yes, I can do that. Now, Frank and I had to put up the five million to make it, so we went to a bank to borrow it. We put our salaries in the movie as well, so neither of us got paid.

We weren’t going to get any stars and we had to make it in Los Angeles. Then MGM said they needed assurances for their five million dollars. They wanted Cheryl Ladd in the movie. Because they could sell it to Japan and make their money back. Now, I love Cheryl, but I didn’t want her in the lead role because she was a television star. She’s doesn’t sell one ticket for a movie. And MGM said: Well, she does in Japan. So, I agreed.

The deal was that MGM had ancillary and Frank and I had theatrical, because we financed the movie. We were guaranteed twelve hundred prints, but they ended up doing two hundred prints for one weekend. Because they had made a presale to Lifetime on ancillary. All legal, but they did it behind our backs. And here’s the thing: in that weekend, it did between six and eight thousand per screen. Do you know what kind of box office that was? They spend zero on advertising and still, that weekend, there were girls lined up around the block waiting to see the movie. After that weekend, they shut it down. They didn’t want to support it, because the theatrical money was gonna go to us. It was so crushing. That’s why I went into television after that.

Tanya Fenmore and Staci Keanan in Lisa

Did Lifetime show LISA as it was? Or did they make cuts in the climactic scenes of the movie?

No, they showed it exactly as it was. I think it’s one the biggest accumulative ratings on Lifetime. They still run it.

Are you satisfied with how LISA turned out?

The movie itself looks a bit like a television movie. I didn’t have the time or money to do the kind of camera moves I’d like to do. I literally saved up money so we could have a Louma crane for that last shot, where we pull back from the two women back to the phone. The Louma crane was a brand new device that no one really knew how to use, so it somehow resulted in a bump in that last shot, that I didn’t know was there, because we didn’t have video assist back then. But we didn’t have the money to go back and do a reshoot. That’s why there’s a dissolve in that last pullback shot. I cringe every time I see it. I hate dissolves, especially when they’re used as a piece of tape.

But I like the film. It’s one of my favorite things I’ve written. It’s so today. It’s such a woke movie. MGM wanted the Cheryl Ladd’s character to have a boyfriend and they wanted the boyfriend to come in at the end then save them from the killer. But I said: Fuck that! It’s two women and they’re going to save themselves. This is a story about a mother and a daughter, and it’s their ingenuity and strength that saves them. Not some guy.

And what did your daughter think of the movie?

She loved it. She was very proud of her dad.

Gary Sherman (left) and Frank Yablans (right) on the set of Lisa

Related talks

Special thanks to Mari Mur for letting us use two of her photos, taken when Gary Sherman visited the Night Visions Film Festival in Helsinki, Finland in 2017. You can follow her photography and her artwork on Instagram.