KILLER INSTINCT

DAVID MORRELL

Photograph courtesy of David Morrell

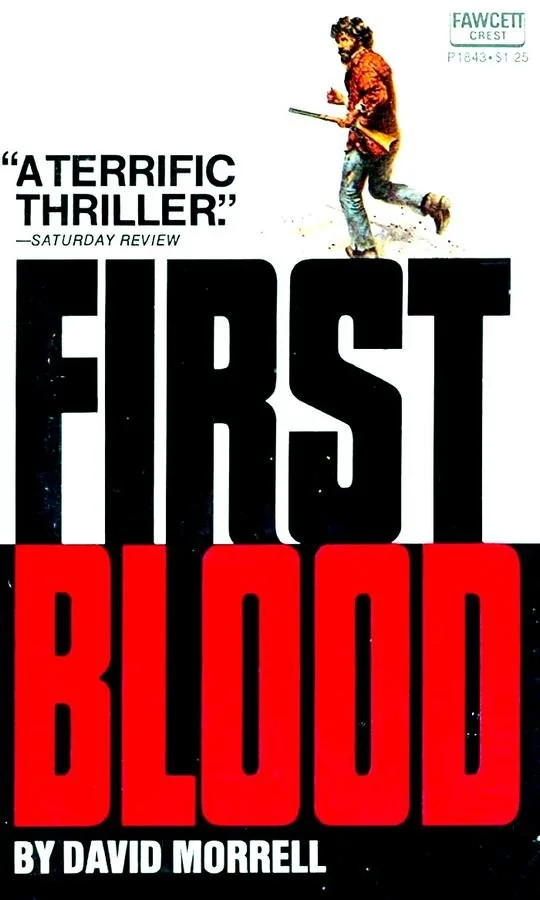

In 2022 it’s exactly fifty years since David Morrell’s novel First Blood was published. It has never been out of print since. It took ten years and a couple of tries for the movie version to get made, but when FIRST BLOOD was finally released, it was one of the most influential action movies of the 1980’s, spawning a number of sequels that made Morrell’s creation a defining figure of that time. Morrell also wrote the novelizations of the first two sequels and has talked with Sylvester Stallone on a number of occasions about ideas for sequels, none of which came to fruition. Morrell has been a successful writer for half a century now, publishing more than thirty books, most of them action thrillers and mystery novels. Because this is a movie website, the talk Roel Haanen had with him in January 2022, via Zoom, concentrates on FIRST BLOOD, the Rambo character and sequels, Morrell’s experiences in Hollywood and the impact the Vietnam war had on Hollywood.

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of your novel, First Blood.

Yes. Any author who sits down to write a book and says it will still be in print after fifty years is hallucinating. It doesn’t happen very often. A couple of years ago Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby was fifty years old and the publisher asked me to write an introduction for it. I was a literature professor for many years and I enjoy writing about books. So, I wrote an essay. And I thought it was just wonderful for Ira, even though he wasn’t around to enjoy it. Now here I am, in the same position.

What, in your opinion, gives First Blood this lasting power?

When I started First Blood I was a graduate student at Penn State University. I had come to the United States to study with a Hemingway expert named Philip Young. I always wanted to be a writer, either a novelist or a screenwriter. It turns out I didn’t go into that latter direction very much. I have written for movies, but it’s not what I primarily do. Anyway, I had this idea that Hemingway, when I looked at his work, could be considered an action writer. He had written several war novels – For Whom the Bell Tolls, A Farewell to Arms – and gangster novels, like To Have and Have Not. There was a lot of action in the other books as well. When I read those action scenes, it was like no one had ever written action before. None of the clichés or pulpy ways people normally write action were in his work. I thought: Could I do that? Not that I write like Hemingway or that I wanted to imitate him, but could I write an action book that felt real, that has a freshness to the expression that would make it different? I still read in action books things like: A shot rang out… Gun smoke filled the air, even though ammunition hasn’t produced gun smoke for a very long time. People aren’t even trying. It drives me crazy. That’s why First Blood still feels fresh when you read it today. Also, Hemingway said: don’t use contemporary slang, because your work will be dated. If you have to use slang, invent your own. That’s what I did.

On top of that there was the social structure. There’s no social or political dialogue in the novel, but the plot itself illustrates how different factions can stop talking and only react to each other. That is something we still see play out today.

About that polarization: the novel alternates between Teasle and Rambo and both men are morally responsible for what happens. That reflected American society. As the writer you seem to take up the middle ground. Was that also true for the debate itself? Did you take up a neutral position?

Yes, I did. Because I was Canadian. I’m now also an American citizen, but when I moved to this country in the mid-sixties, as that violent debate erupted, I was firmly reminded by the customs officer that this was not my country and that I had no right to political opinions. People don’t do this enough. I have been in social situations where I visited other people’s homes for a party or dinner and an argument breaks out over politics. And my God, they keep arguing! Even though one of them is a guest. When I’m a guest I will just say: I respectfully disagree and let’s change the subject. So, there I was as a Canadian in the United States, watching unfold what I thought was going to be a civil war. That’s why I thought of the character of Sheriff Teasle as a 1950’s Eisenhower Republican, a conservative. And Rambo, who hated himself for what he had become in the war, was the opposite. At the time you had the Students for a Democratic Society who were extremely violent. I thought of Rambo as a war protester. In the middle we have the system, as represented by Colonel Trautman, whose first name, of course, is Samuel, like Uncle Sam. In the novel it’s the system that destroys Rambo. Those were the things going on in my mind. So, the two main characters, Rambo and Teasle, are like two trains coming at each other. But other than the plot itself, I didn’t put any politics in the book.

I don’t mean to psycho-analyze, but I was wondering if the death of your father, who died on D-Day, influenced the character of Teasle.

You’re quite right. My life was very much controlled by the events relating to my father’s death. I did not know him, I was very young. I was born in 1943, he died in 1944. He was a British trainer of pilots in Canada. That’s how he and my mother met in Ontario. I have since learned that he probably died the day after D-Day. He was an aerial observer. His job was to fly over the French coast to see where the British naval bombardments were hitting and then tell them when they needed to correct the trajectory of the barrels on the ships. He was shot down.

My mother was not able to support us both, so she was forced to put me in an orphanage, which defined my personality. I was in the orphanage at the age of three for a year. Ever after I kept wondering if she reclaimed me, or if this was someone who had adopted me. All this confusion. She remarried, but her new husband did not like children. We didn’t get along and I actively dislike the man to this day. When I was a professor a student of mine said someone could write a thesis about the many father-son relationships in my novels. In First Blood, Teasle is old enough to be Rambo’s father. His wife has left him, because he wanted a child and she did not. Now here comes this young man who’s young enough to be his son. At the time, the generation gap was a big thing, so this was an intentional part of the book.

The way Teasle thinks about Rambo, as if to say: If only the kid would listen to me!

You got it exactly. We do know that Rambo’s father beat his mother and himself. It’s one of the reasons why he entered the military, to get away from all that. Certainly, Trautman was a kind of foster father to him. That theme is picked up in the movies. But I didn’t want Rambo to think about Teasle in that way, like: First my father beat me, and now this guy… That’s tiresome. But it is there, between the lines.

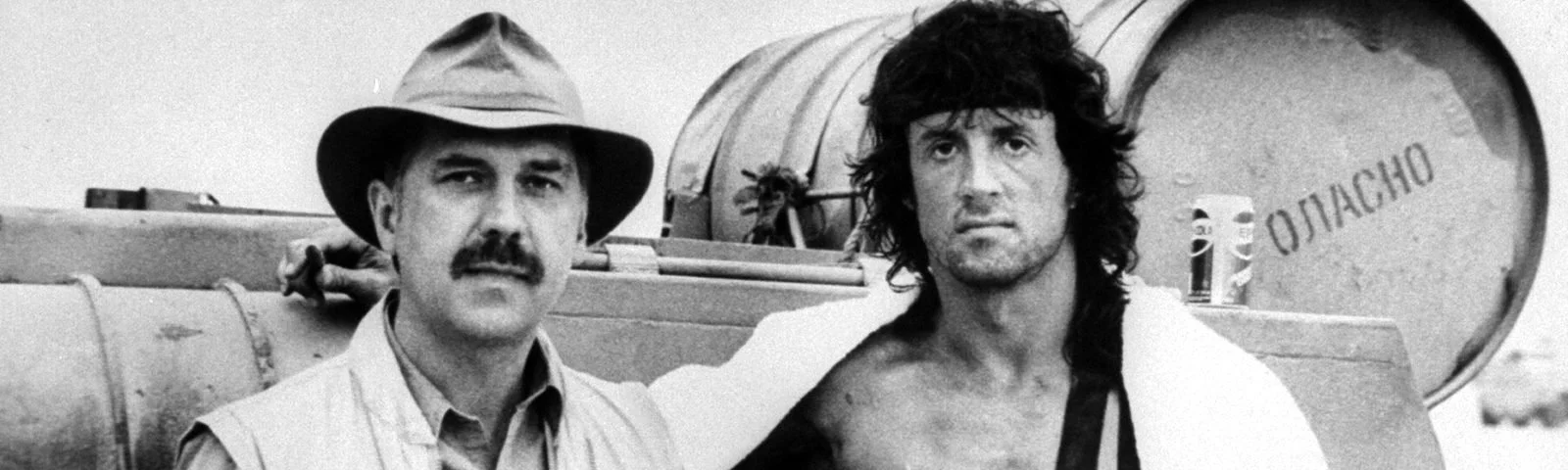

Sylvester Stallone as Rambo and Brian Dennehy as Sheriff Teasle in First Blood

After the book was published, there were a number of attempts to get it filmed. How far did these attempts go? Was there ever one that was really concrete, with a director and star attached?

Yes, one extraordinary possibility was that Sidney Pollack, who is one of my favorite directors, worked on a version of FIRST BLOOD for six months for Warner Brothers. I know this because he told me, when I spoke with him at length during a film festival. The big news was that Steve McQueen had agreed to play Rambo, because he wanted to do the motorcycle stunts. But as they prepared the film, they realized – and this happens a lot in the movie business, where they suddenly realize something – that McQueen was too old. He was in his mid-forties. Unlike in recent American wars, in which military personnel can be middle aged, in Vietnam they were all just kids. If you were twenty-one you were old. A Vietnam veteran in his mid-forties was not believable, so the project was abandoned.

As a professor, I love to dig into the background of things, and what I could uncover was that there were twenty-six different scripts for different productions that were prepared. Richard Brooks was the first director to take the project on. He and I talked about it, but we had a difference of opinion about the story and he refused to talk to me after that. But he was going to make it right then in 1972. For whatever reason that didn’t move forward, and then it went to Warner Brothers where Martin Ritt was going direct Paul Newman as Teasle. This is something I heard in conversation. I have no proof of that, like I have with Pollack, where I have his own testimony.

It went through these turnings and then a company called Carolco, which was headed by Andy Vajna and Mario Kassar, came into the picture. I knew Andy well. I had been to his home. They had a relationship with Ted Kotcheff. They asked him what movie he would like to make for them. And he said he had worked on FIRST BLOOD over at Warner Brothers, but it didn’t get anywhere. So, then Andy and Mario bought the rights and Ted signed on.

What was your disagreement with Brooks about? Do you remember?

I do remember. I had been flown to California to meet with Richard at his home, which was a lovely, big estate in Bel Air, complete with a huge screening room. It had an office in the back and that’s where we had the meeting. I was twenty-nine and I was dressed wrongly for the California weather. I was a professor in Iowa and I had a suit on, on a Sunday afternoon. Brooks had on what looked like a butcher’s uniform. I swear to God! It was like a white smock. What I’m about to say is no disrespect to him. I love his work. He made great, good-looking movies. But this is how he wanted FIRST BLOOD to end: Teasle and Trautman approach Rambo, while soldiers and national guardsmen are surrounding him. And as Teasle approaches, somebody fires a gun accidentally. Then everybody fires their gun. Teasle dives into a ditch with Rambo. The bullets turn up the dirt above them. Teasle turns to Rambo and says: You know, none of this would have happened if only we tried to understand each other… Now, that is bad, right?

Really bad.

There was an embarrassing silence. There was someone else in the room with us, Lawrence Turman, who had been a producer on THE GRADUATE. He was going to produce FIRST BLOOD. Brooks said: What do you think of that ending? I said: It reminds me of a western I saw the other night, in which the Indians and the cavalry have a standoff and the cavalry guy rides up to the chief to have a talk and a shot rings out and they all start shooting. It’s not a bad idea for a first draft, but I do think there’s a better way to end the picture. He looked at me and raised his right hip, as if he was breaking wind. And then the phone rang. I immediately realized he had a button under his desk that could make the phone ring. He picked it up and said: Yes… yes… yes… And he hung up. He said that his mother-in-law called and he had to drive her to the airport. [Chuckles] You can’t believe this stuff! Before we knew what was happening, Turman and I were on the street. The next day I got a call from my agent, who had been called by the head of Columbia Pictures, to inform me that the only time Richard Brooks wanted me to have anything to do with this movie was when I paid my money to go see it.

What a crazy story!

Yeah. There’s a book on Richard Brooks in which I tell that same story. That was my introduction to Hollywood. Later people denied that conversation happened, but it definitely did. But again, I don’t mean any disrespect to Brooks, he truly was great filmmaker: ELMER GANTRY, THE PROFESSIONALS, BITE THE BULLET. The list goes on.

David Morrell (left) with Carolco boss Andrew Vajna. Photo courtesy of David Morrell

Let me ask you about the difference between the novel and the film. They’re both masterpieces of their respective crafts. What makes the movie great is not what makes the book great, and vice versa. Another example of that would be Stephen King’s The Shining and Kubrick’s movie. In both cases, you could argue that the movie misses the point of the novel, but whereas King hated Kubrick’s film, especially for that reason, you don’t hate Ted Kotcheff’s movie.

No, far from it. What you said is my viewpoint. Movies are different from books. One of the reasons FIRST BLOOD couldn’t get made in the seventies, was the way the Vietnam war was perceived in Hollywood. The feeling was that the war was a big mistake and that it had damaged America, which it did. So, what you got were films like COMING HOME and THE DEER HUNTER. But when Ronald Reagan assumed the presidency in the eighties, he basically said: Let’s forget the seventies, let’s forget Vietnam. They’re always making America great again, right? What Andy and Mario did, was to make FIRST BLOOD for an international audience. They had relationships with a lot of foreign distributors. They cut about fifty-two minutes of action, showed it to overseas buyers and sold the movie all over the world. They changed the business that way. So, they were making a movie for an entirely different audience than COMING HOME or THE DEER HUNTER.

One of the problems was that the violence in my novel is considerable. Rambo does indeed prove he is an expert at warfare. The assumption was always that Rambo was going to be the main character in the movie, other than in my novel, in which we spend almost equal time with both Rambo and Teasle. The question was how to make him sympathetic. So, they invented this opening scene in which Rambo walks up to this black woman who’s hanging the wash outside and he asks about his friend. Right away you have an inclusion theme. Rambo is a friend of everyone. Now we find out that the friend he’s looking for has died of Agent Orange. Oh my God! He’s so heartbroken. And that’s when the police hassles him! And Sly has these wonderful deer eyes. You just have to sympathize with him.

There’s a funny story about that opening scene. I was meeting with someone from a studio in a restaurant. Mark Rydell was there, who had directed THE COWBOYS. And Mark knew the guy I was having lunch with. So, the guy introduced us. After lunch, Mark and I were outside waiting for our cars – because that’s what you do in Los Angeles, you don’t park your own car – and Mark turned to me and said: You know, you’re a really good writer. I said: Oh, thank you, Mark. He said: Yeah, that opening scene in FIRST BLOOD, where he visits his friend’s family and you stack up the sympathy, that’s really great writing. What was I gonna say? I said: Thank you, Mark. [Laughs]

About Stallone’s performance, he not only gets your sympathy right away, but his performance is so physical. He’s instinct personified.

The reason for that, apart from the obvious, which is that action speaks louder than words, is that they wanted to keep the dialogue to a minimum, because it was easier when they had to translate it to different languages. Andy Vajna told me this. It turned out to be beneficial to the movie.

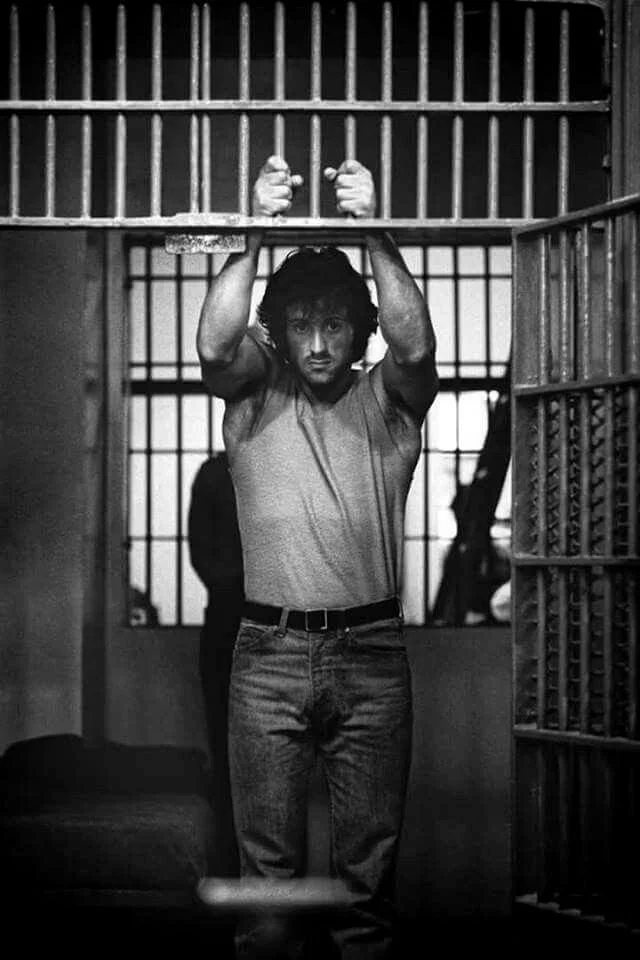

Stallone in First Blood

It is one of my favorite movies of all time. I saw at a young age in the theater. It still blows me away.

Yes, it is one well-made movie. From the cinematography to the direction. The script is very nice. And the score by Jerry Goldsmith transcends it all. He was the best. My only criticism is that I think the language is needlessly vulgar. Some of the expletives need not be there. Maybe those are my sensibilities, but on the other hand, I never object to Tarantino’s dialogue. I admire his work enormously. So, I don’t object to vulgar language, but I thought in this case in interfered with the tone of the story.

Speaking of Quentin Tarantino, he’s also a fan of your novel.

Yes. In fact, when Tarantino promoted his novelization of ONCE UPON A TIME IN HOLLYWOOD he said that if he would do a remake, he would make one of FIRST BLOOD. And he explained that he would do the novel. He mentioned how he loved the dialogue. He had it cast in his head, with Adam Driver as Rambo and Kurt Russell as Teasle. I was really thrilled. Sadly for me, he doesn’t do remakes.

There has already been one faithful adaptation of First Blood, which is called FLOODING WITH LOVE FOR THE KID. You’ve seen it, I believe.

Oh yes! I have been in contact with the writer-director-performer, Zachery Oberzan, who is a huge fan of the book. He had an off-Broadway play in which he acts out the whole story by himself, using stuff in his apartment. I thought it was just terrific. He had my permission to do it.

I used to be a festival programmer in Amsterdam and we had Zachery Oberzan and his film over. He’s an interesting guy.

Absolutely. Very gifted man. Very passionate about film and stories in general and, luckily for me, passionate about my book. I had a couple of lunches with him when I was in New York. I loved what he did with First Blood and I even gave it a blurb when it came out on DVD.

Stallone in First Blood

In the seventies there were a number of films that dealt with veterans having difficulties adapting: COMING HOME, ROLLING THUNDER, WELCOME HOME SOLDIER BOYS, THE DEER HUNTER. Did any of them capture some of your own sensibilities about what happened?

Clearly, COMING HOME was about Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome, which wasn’t defined as such at the time. THE DEER HUNTER also deals with that to a certain extent. But what was on my mind, when I wrote the novel, was Audie Murphy. He had been America’s most decorated soldier in World War II. His citation for the Medal of Honor is extraordinary. It’s superhuman. Anything Rambo has done in any of the movies pales in comparison. He was a young kid when he went into war. A little sweet-faced kid from Texas. But he found that he had the killer instinct, that if he had to do it, he could really do it. In one of those meta-moments worthy of Tarantino he played himself in the movie TO HELL AND BACK, based upon his own book. In some of the action scenes in his movies, you could see something in his eyes that suggested that maybe he was back in the war.

I’ve written about him. Turns out he lived a miserable life. He suffered from PTSD. He kept a weapon under his pillow. He woke up from nightmares, screaming and shooting. There were bullet holes in the walls that they would cover up by moving pictures around. He was accused of attempted murder for having pistol-whipped a dog trainer who had supposedly overcharged a friend of his. There’s a story about an assistant-director who would belittle Audie’s female co-star and made her cry. He went over and said: If you make her cry again, I’ll kill you. Apparently, when Audie Murphy said that, you believed it. He had an unsuccessful civilian life. He once said that he had wanted to write a second book, about adapting to peace time. So, that was one of the impetuses for writing First Blood. What if someone like Audie Murphy came back from Vietnam, with all the unpopular feelings about the soldiers. This fascination goes back to my youth, about what you asked me earlier, the consequences of World War II.

COMING HOME, APOCALYPSE NOW and THE DEER HUNTER were all made in the late seventies, when the war was over. But there had been a few westerns in the early seventies that were influenced by Vietnam, like SOLDIER BLUE and ULZANA’S RAID. That was probably an easier way for Hollywood to comment on the war.

Without question. In fact, Robert Aldrich, Burt Lancaster and Alan Sharp, a fantastic writer who also wrote NIGHT MOVES, they all said that ULZANA’S RAID was a Vietnam western. That was not a secret. They were trying to translate the Vietnam experience, as they understood it, to the western format. For people not familiar: in ULZANA’S RAID, which is one of my favorite westerns and favorite films, Lancaster plays a cavalry scout who is helping a young West Point officer to lead an army unit to bring back a band of Native American warriors who have escaped the reservation. It presents a really bleak view of things, other than SOLDIER BLUE which has a more pacifist viewpoint.

I would also say THE WILD BUNCH is a Vietnam western. Because the Vietnam western morphed out of something called the Americans-in-Mexico subgenre, where you have Burt Lancaster and Gary Cooper in VERA CRUZ, you have Richard Brooks’s THE PROFESSIONALS, again with Lancaster, and you had THE WILD BUNCH. Then there’s a not very good one with Burt Reynolds and Raquel Welch called 100 RIFLES. That movie has a lot of problems, but if you look at it through the theme we’re considering, it’s an important film. Because in the end, after all that has happened, after all the revolutionaries that have been killed, after Raquel’s character has died, Jim Brown says he’s going back to the United States to fight for civil rights. And what does Burt Reynolds do? He gets in cahoots with the railroads! He becomes a capitalist. All that revolutionary stuff didn’t matter. It was never about ideology, it was all about money. Now, if you look at Vietnam, that war didn’t make any difference either, historically. Because even though the U.S. lost the war, Vietnam is now just as capitalist as we are. So, you can take all of these Americans-in-Mexico westerns and they lead right into films like SOLDIER BLUE, ULZANA’S RAID and other Vietnam westerns. There’s a wonderful book called Still in the Saddle by Andrew Nelson, in which he analyzes westerns from 1969, when THE WILD BUNCH came out, through 1980 and the failure of HEAVEN’S GATE. That becomes a distinct chunk of movie history.

Burt Lancaster and Bruce Davison in Ulzana’s Raid

Let me ask you about the Rambo sequels. There's a strange paradox that surrounds RAMBO: FIRST BLOOD PART II. The movie acknowledges that the war was lost, that it’s a national trauma and that the American government has been deceitful when it comes to sending young men into that war. In fact: the government is again deceitful when it sends in Rambo to find the POW’s. Still, a lot of people took this movie as a Reagan-era symbol for American supremacy. On the surface, I can see why, but it doesn’t make much sense if you think about what the movie actually says. What is your take on this?

This conversation is fun, because you get this stuff. It’s true: it is a much more complicated film than people allow. The big deal in the beginning is when Rambo asks Trautman: Do we get to win this time? That line overshadowed everything. Together with Rambo’s speech in the end, where he talks about making sacrifices for your country, those two bookends caused some people, including Ronald Reagan, to ignore all the stuff in the middle where the United States has been deceitful. There’s dialogue about it.

But it cannot be denied that the character is not the same as in the first movie. Rambo’s not the same guy. He had changed to fit the times. The second and third movie, where he’s gonna save Afghanistan, are of a pair, in that they contain a character that is in many ways the opposite of the character from FIRST BLOOD. The Rambo from FIRST BLOOD wouldn’t ever pick up a weapon again.

It was fascinating to see how the character from my novel, in which he’s really angry and bitter, changed to a really sympathetic guy who just wants to be left alone in the first movie, and then to a guy who will fight when provoked and who maybe even enjoys it.

Ronald Reagan really used the character as a symbol.

That’s right. Reagan frequently referred to Rambo in press conferences. The one I remember distinctively is when Reagan said he had seen a Rambo movie the night before and now he knew what to do the next time there was a terrorist hostage crisis. Another one I remember was when the U.S. had bombed Libya. I was in London, preparing to go on a morning talk show when I glanced at the headlines. It said: U.S. Rambo Jets Bomb Libya. It was somehow absorbed into the culture. Rambo became identified with America’s military policy.

Did that bother you?

Yes, it did. Because in the United States book stores tend to be owned by liberals. I don’t like to think in these terms, I think of myself as an independent voter. But a lot of book stores refused to stock my books in the latter part of the eighties for political reasons. But I persist in my beliefs and I’m still here.

But as a literature professor, who’s interested in American culture and society, I found it really interesting. Moreover because it concerned my own creation. One of the reasons I wrote the novelizations for RAMBO: FIRST BLOOD PART II and RAMBO III is that I saw where this was going. And because I was the only one who could write books about the character – that was in my contract – I thought it could be an interesting challenge to see if I could write a novelization that was closer to First Blood. And it was a challenge, because the script for the first sequel was just eighty-six pages. That’s how short it was, with a lot of white space. These are real quotes: Rambo jumps up and shoots this guy. Rambo jumps up and shoots that guy. Luckily, I could also draw upon the version of the script that James Cameron had written, which they didn’t use. I used those two versions of the script and then put in my own ideas as well. I really enjoyed writing those novelizations. The one for RAMBO: FIRST BLOOD PART II was on the New York Times bestseller list.

You’ve said about RAMBO III that you thought it was a bit too old fashioned. Could you elaborate on that?

I was on the inside for that one. The original script was wonderful. The joke on the set was that this was going to be Rambo of Arabia. That was the script I was given to novelize. The basic premise is the same as the finished movie: Trautman has been kidnapped and Rambo goes after him. He bonds with the Afghan tribe. In the script there was a Joseph Campbell type sequence in which Rambo is reborn when a sandstorm overcomes him. Just like him coming out the bat cave in First Blood. Then there was a Belgian or Dutch female doctor, who was taking care of the orphans who were seriously injured by the war. Without any romantic implications Rambo sympathizes with her. In the second act Rambo rescues Trautman. In the third act he leads the injured children, some of them without limbs, together with the doctor and Trautman, over a mountain, through a snow storm, to get out of Afghanistan, as they are pursued by the Russians. I get chills even thinking about it. It was good. But each new draft cut back.

Some of it was out of budgetary reasons. Because when they decided to film in Israel, they were cheated by people who promised facilities which turned out to be rusted warehouses. They weren’t sound stages at all. They had a lot of footage that was shot by a different director which they deemed unusable. Whether it was or not, I do not know.

That was Russell Mulcahy, right?

Yes. I don’t know what the story was there. But they brought in Peter MacDonald. Very nice man. And a gifted director. But by then the budget didn’t allow for the third act. So, what it became was: Trautman is kidnapped. Rambo tries to rescue Trautman and fails. Rambo tries to rescue him and succeeds. The third act was inherently weak and repetitive. It could not have been a good movie. But the novelization uses the original script and emphasizes the idea that Afghanistan was Russia’s Vietnam. I brought in all of that. I had a Russian counterpart of Rambo, who was his equal in guerrilla warfare, and who was experiencing the same disillusionment. I know that Andy [Vajna] and Mario [Kassar] did their best on this movie. They were first class.

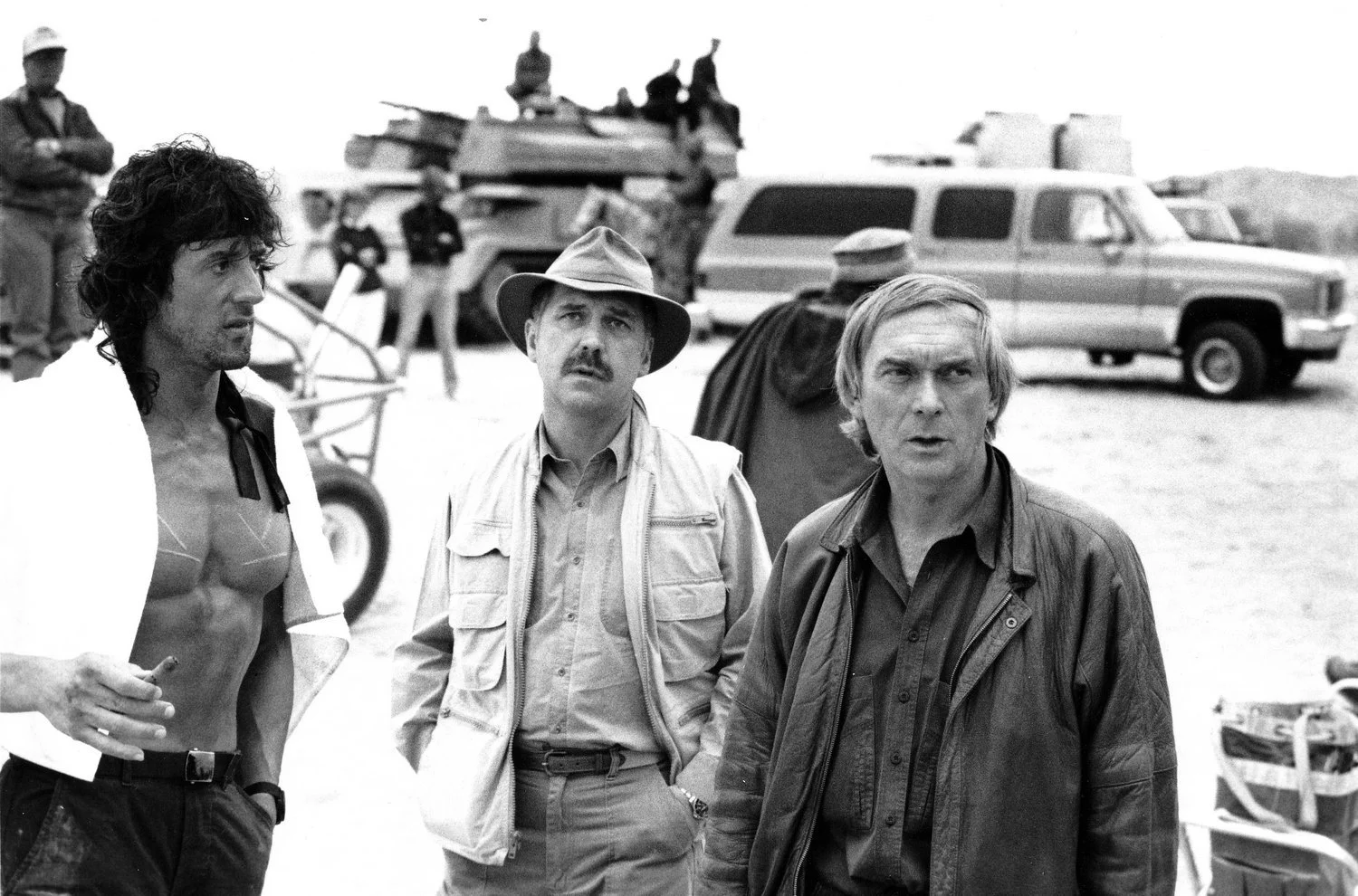

From left to right: Stallone, Morrell and Peter MacDonald on the set of Rambo III. Photo courtesy of David Morrell

The fourth Rambo is terrific, I think. It goes back to the origin of the character.

Yes. Sly and I talk on occasion on the phone. We’re not friends. I’ve never had dinner with him, for example. But sometimes he needs someone to act like a sounding board, to bounce ideas off of. He called me one time and he said he had an idea for a fourth Rambo movie. He said that in retrospect he thought the second and third movie glamorized warfare, in a way he wasn’t comfortable with. He wanted to make a Sam Peckinpah type Rambo movie, that would emphasize the harsh reality of battle, and he was using my novel First Blood as the model for the tone. The character would be much like the character in the novel.

There are two versions of the film. The theatrical cut is very streamlined, but the director’s cut is pretty remarkable in what it says about war. There’s great dialogue in there. For example, Rambo says: Wars. Old men start them. Young men fight them. Nobody wins. At one point, while Rambo is making the machete, he’s remembering the war. And he says: You didn’t kill for your country, you killed for yourself. And for that, God will not forgive you. That is hard to imagine in a Rambo movie. No critic picked up on this. I’m sure they already had their ideas and this didn’t fit their template.

If I had to criticize the movie, I’d say the final battle scene is too long. The production company were making the films for various international markets and in some parts of Asia they like these long battle sequences. And because this is a Sam Peckinpah Rambo movie, you have a version of the big machine gun that William Holden uses in THE WILD BUNCH.

You didn’t like the fifth one. I think we agree that it doesn’t feel like a Rambo movie at all. It’s more of a generic revenge thriller. But I was surprised that you saw the parallel between this movie and the little known TRACKDOWN, which I had seen thirty years earlier, but had mostly forgotten.

I was surprised that nobody realized that it recycled the story of TRACKDOWN. I noticed immediately. But LAST BLOOD is a preposterous movie. If you look at the first movie, Rambo goes crazy in a jail cell. He has flashbacks to Vietnam where he’s in a hole in the ground with people throwing garbage on him. Later on he’s trapped in the mine with rats. Does it make sense that a man who we know is claustrophobic would be living in a hole in the ground? Now, you could say he’s testing himself. But that’s not in the movie. If that was the idea, you’ve gotta earn it. Would the man, who in one film says that the mind is the greatest weapon, who is supposed to be this master tactician, walk up to the main bad guy, who is surrounded by hundreds of bad guys, and expect that on the strength of his burly figure they would just give him his niece back? The only reason he does that is that the audience needs for him to get the hell kicked out of him, because they need the anger for the rest of the movie. I don’t know what to make of that movie. It’s certainly no Rambo movie. It’s not part of the canon.

Rambo (2008)

Do you expect or hope that Stallone takes one last stab at the character to give him a proper send-off?

I don’t think he will or can. The year he made CREED in Philadelphia, he called me one day. He wanted to make a final Rambo film. And for weeks we worked out a plot that was heartbreaking. This was a film festival movie, an award movie. I can’t talk about what the story was, but it was a perfect ending.

Are you legally prohibited to talk about it?

No, I just don’t want to. You could see where this conversation would go. If I talked about what our idea for the movie was, you’d get a response from a lot of people, saying: That is not a Rambo movie. If it was presented as the new movie, it would be another matter. Now, later on, when I read that Sly was making the fifth movie, I texted him and I asked: Is this a version of the idea we talked about? And he texted back: What idea was that? This was after about fourteen hours of conversation between us.

Unbelievable.

Now, this is not about Sylvester Stallone. This is about how the movie business works. When my son Matt was dying from cancer, he had some friends over and Sly happened to call. I had asked if he would, through his people, and Sly had said he didn’t know what to say. I told him that my son was a movie buff, so all he had to do was talk about movies. The first thing my son asked him about was the grosses on his latest movie. They talked about the movie business, while his two friends sat in the kitchen watching him talk to Sly Stallone. For that I’m eternally grateful. So, when I talk about that text that is the movie business. That would have been the response from any actor I would have been dealing with.

With Stallone on the set of Rambo III. Photo courtesy of David Morrell

I’ve read that there’s an idea for a Rambo television series. Do they have to ask your permission for that or do they automatically have the right because they own the movie character?

They own the rights. In 1995 Carolco – God bless ‘m – went bankrupt. Their ambitions were too great. It’s hard to believe that the people who did TERMINATOR 2: JUDGMENT DAY, TOTAL RECALL and the RAMBO movies would go bankrupt, but they made CUTTHROAT ISLAND. It’s not a bad movie. The stunts are great. Poor Geena Davis had to really knock herself out to do the stunts. But it just wasn’t the right time. At the bankruptcy auction, the rights were divided. There was the right to further exploit the existing Rambo movies and the right to make future Rambo movies. They were sold separately.

Miramax had the right to make new films for about eight years. They called me one day and said: We’ve been trying to make new Rambo movies, but it’s not going anywhere. We don’t know what we’re doing wrong. I asked them about some of the plots. One plot had Rambo in Iraq fighting a battle. And during the battle, he discovers a treasure. So, after the battle Rambo and his men try to dig up the treasure. And then they had another one where Rambo was a mercenary. It was all really bad. I told them: What am I hearing? These are not Rambo movies. So, they flew me to New York for a meeting with Bob Weinstein. We were there for about six or seven hours, trying to sort this out. They paid me to write a treatment which was never used, but some elements of it later wound up in LAST BLOOD.

Miramax got into trouble and they sold the Rambo rights to Millennium / Nu Image. And they have the right to make a television series. The problem is, Vietnam was so long ago, a lot of viewers don’t even remember what it was. So, the idea is to keep updating it. But there have been so many wars, which war is he getting back from this time? I suspect that world events will constantly outdistance the possibility of a TV series. Plus, they will probably make him a save-the-world-character, whereas Rambo truly is a guy who says: I hate what war did to me, please don’t make me do it again. They’ll turn him into a Tom Clancy character. They won’t talk to me about it, so whatever.

By the way, there already was a series, a Saturday morning cartoon, in which Rambo sits around in the forest, talking to little bunnies. Really terrible.

One last question. You’ve also written for Marvel. Are you into the Marvel Cinematic Universe as a viewer?

I’m not. I was called by Marvel. They wanted the creator of Rambo to write about another iconic American military figure. So, I wrote six episodes of Captain America: The Chosen, which was then assembled in book form with an afterword by me, explaining how you write comic books and what I wanted to accomplish. Then I wrote a two-part Spider-man and a Wolverine. I loved doing them.

My feeling about the superhero movies of today, is that they’ve become firework shows. Compare the Christopher Nolan Batman movies with what you see now. There was a lot of angst in those Nolan movies. I was reading the other day that Michael Keaton left BATMAN FOREVER because the director wanted to camp it up. And Keaton said: No, this is about a guy who’s so tortured he dresses up as a bat! I saw many of the Marvel movies and after a while it became clear to me that the movies were made to please this segment of the audience and then that segment. And they just kept adding fireworks. I thought the first WONDER WOMAN was a model for how good a superhero movie could be, except for the far too long climax. The second WONDER WOMAN was about as bad as a superhero movie could be. The villain in a tinfoil suit… Come on! The first ten minutes were wonderful, but then the plot took over. I hear good things about the new SPIDER-MAN, but I’ve been burned so much, seeing bad superhero movies, that seem only to have been made for the completists. But I sure loved that first WONDER WOMAN.

This talk was edited for length and clarity.

Thanks to Barend de Voogd for his help preparing this interview.

Special thanks to David Morrell for letting us use some of his photos. You can find out more about David’s novels on his website: www.davidmorrell.net